The recent presentation of the French government’s anti-pollution plan was an opportunity for many in the media to remind us of a significant figure: air pollution from fine particles is estimated to cause 48,000 deaths per year in France. Despite its surprising nature (this would mean that about 9% of all deaths were caused by pollution), this figure was treated with few reservations in the press, and even less in political circles (Anne Hidalgo had already used this argument in 2017 for the City of Paris’ anti-pollution plan) It is true that it comes from an irreproachable source, as it is a report by the Agence Santé Publique France (SPF)[i] [Public Health Agency France], which estimated the number of premature deaths attributable in France to PM 2.5 particles (particles with a radius less than or equal to 2.5 micrometres), using a new mathematical model, based on a map of spatialised air pollution over the entire French territory, at the municipal level. But can this figure of 48,000 deaths be taken as a basis for consideration without reservations? And what exactly does it measure? A careful reading of the SPF report reveals some surprises…

A range of uncertainty between 11 and 48,000 deaths!

The first note of caution (the only one mentioned in the SPF press release, and therefore the only one sometimes taken into account by the more vigilant media) is to state that 48,000 is only the top of a particularly gaping range of uncertainty. In fact, the number of premature deaths calculated by the SPF model varies considerably according to the basic level of pollution considered as “normal”: from 48,000 annual deaths if we take as a reference the least polluted parts of French territory… to 11 deaths if we take as a reference the threshold of fine particles recommended by the WHO ! It is clear, however, that SPF clearly favours a maximising interpretation of 48,000 deaths, and this is the only figure cited by most of the newspapers that reported on this publication. Even if the SPF does not express it very explicitly, it therefore amounts to severely criticising the current standards on air pollution. The INVS [Institut de veille sanitaire, Public Health Surveillance] (now part of SPF) had already questioned these standards in a previous study, which focused on short-term deaths caused by pollution[ii] peaks… forgetting in passing its own work on the effects of the heat wave (the short-term effects of pollution tend to occur only during summer pollution peaks, and not in winter[iii]).

A purely theoretical result, presented as an established truth

On such a serious subject, it therefore seems necessary to examine the arguments and the method employed by SPF in meticulous detail. From this point of view, the report presents some surprising gaps:

- It contains NO results validating the model used, i.e. no comparison between the mortalities calculated according to their model in each commune, and the actual recorded mortalities. When the authors tell us that their model is an accurate representation of reality, we are therefore obliged to take their word for it.

- This calculation is based on the application of a relative risk (RR), which defines the relationship between mortality and fine particle concentration in the air. In the usual publications on this subject, this RR is statistically calculated by combining a mortality data set with pollution data covering the same geographical area. This is not the method followed by SPF, which in this report has calculated mortalities directly from its spatialised pollution map, with an RR chosen by the authors. This choice of methodology is all the more audacious as the value used is very high compared to existing bibliographical references: RR=1.15 for an increase of 10 μg/m3, i.e. more than double the values used by the previous meta-analyses that the authors cite in their bibliography (0.6 and 0.7). The only justification for this surprising choice is that this value has already been observed in France (by the same SPF authors, there being no better reference than oneself…). Why not, but we would still like to know the RR value that would have been obtained directly from the actual mortality data at the commune level. Once again, an essential element for validation of the SPF model is missing from the report.

- To be scientifically sound, the authors show results from a sensitivity analysis, which theoretically allows the robustness of the model’s predictions to be assessed, based on the uncertainty in its input data. Unfortunately, this analysis only covers relatively secondary parameters, and dodges the essential question, linked to the previous point: what is the effect of uncertainty on Relative Risk, in estimating the number of premature deaths? For example, we would like to know what would have happened to the results if SPF had used a more conventional RR of 0.6 or 0.7.

Air pollution versus olive oil

So, the discussions of the results completely obscure the real scientific questions posed by the method used. The statistical model used, like the previous studies on which it is based, calculates geographical correlations between mortality (all non-accidental causes combined) and the level of air pollution. This type of correlation is likely to be affected by obvious but difficult to correct confounding factors:

- Life expectancy is strongly correlated to socio-professional category. In large cities, however, the wealthiest people rarely live in the most polluted neighbourhoods. There is therefore an obvious potential for bias here, especially when working at the commune level in large conurbations.

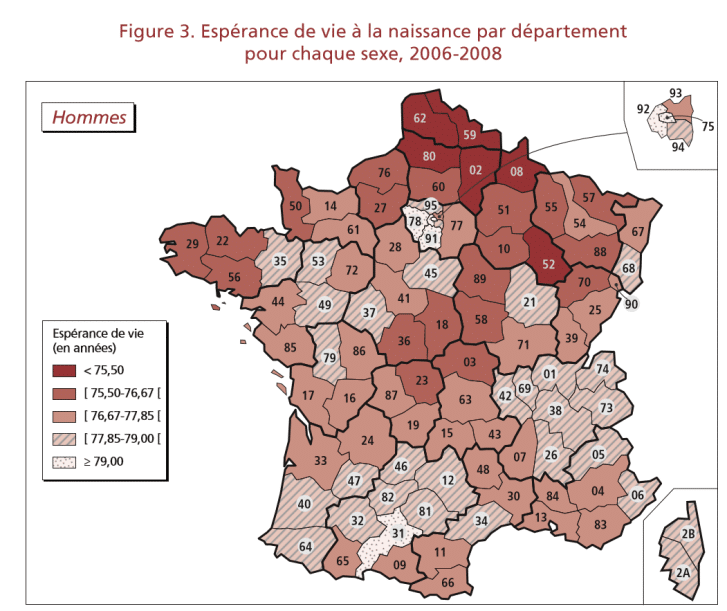

- On the national scale, the least polluted areas are of course rural areas, with demographics, lifestyles, and diet, which are clearly distinct from those of urban populations. It is therefore risky to compare their mortality levels with those of polluted cities. Moreover, in the case of France, this type of large-scale geographical comparison is complicated by regional inequalities in life expectancy, long observed by demographers.[iv] In particular, there is a North-South gradient in life expectancy, which is generally explained by the benefits of the Mediterranean diet. This North-South gradient is also observed for the PM 2.5 concentration. Consequently, the effects of diet, if they exist, could be a confounding factor with the effect of pollution, but this question is not at all addressed by SPF. However, it would be a very necessary question: the effect on life expectancy that they attribute to pollution (3 to 4.5 years difference between the most and least polluted areas) would single-handedly explain the difference between the departments where life expectancy is the lowest and those where it is the highest. Since the supposed effect of diet would go in the same direction overall, and should therefore be added to that of PM 2.5, one of the two effects must be imaginary… or both exist but are both overestimated!

- 1 : On the left, map of life expectancy at birth by department (INED data), on the right the increase in life expectancy in the absence of pollution (SPF – French Public Health Model). The two maps show similarities when viewed on a very large scale (Comparison between the North and East, heavily polluted, and with low life expectancy, and the mountainous areas of southern France). Since the increase in life expectancy calculated by SPF is of the same order of magnitude as the differences in life expectancy actually observed between departments, this would therefore mean that pollution alone explains most of the regional disparities in mortality observed in France. This is of course possible, but still quite surprising, especially since other causes are often proposed for these disparities, such as the favourable effect of the Mediterranean diet. To verify the hypothesis of the dominant effect of PM 2.5 on mortality, it would therefore be very interesting to verify the correlation between mortality and pollution at a more detailed geographical scale. For example, if the “excess mortality corridor” of the Rhône valley calculated by the SPF model is observed in mortality statistics by commune, this would be a decisive argument to remove all doubt on the effect of PM on mortality. Unfortunately, the authors do not provide any validation results for their model.

In addition to these fundamental problems, there are problems of form that are awkward for a scientific publication:

- The authors repeatedly congratulate themselves on the fact that their results are consistent with previous studies, as if this confirmed the accuracy of their work. This is not surprising, however, since the results presented are just simulations of a model based precisely on these previous surveys, and not validated from actual field data. Their claim that their study confirms previous assessments of the health effects of pollution, is therefore perfectly tautological: their model in no way confirms the previous results, it simply applies them on a different geographical scale.

- They use the term preventable deaths several times, which is alarmist language to use, where it would be better to refer to premature deaths. The term preventable death would be acceptable for a disease which is otherwise very rare without a contributory environmental factor (such as pleural cancer for asbestos), but absolutely not in this case.

38,000 dead globally, including 48,000 in France?

In its rationale, this SPF study consequently inclines dangerously towards pseudoscience. The confusing presentation suggests that the mortalities mentioned were calculated from actual mortality data, when in fact they are theoretical simulations run from an unvalidated model, and whose potential confounding factors, though obvious, have not been studied at all. It should be noted that the methodological anomalies we mentioned are not all the responsibility of the authors: they broadly followed recommendations from WHO, which considers the effect of fine particles on health as demonstrated. While the studies on which this consensus is based provide consistent results, this is not surprising since they all use more or less the same method. Before this publication, several other works, not spatialised to such a degree, but based on the same methods, had already obtained results in the order of 40,000 premature deaths per year in France. This estimate has therefore come to the fore, despite its surprising nature (the attribution of 9% of deaths to pollution on national average, up to 13% in large cities). It implies that pollution must be the major determinant of geographical inequalities in life expectancy in France, which contradicts the other explanations considered as well as those clearly demonstrated, the effect of the socio-professional category, and that of the Mediterranean diet. With its detailed spatialisation of the distribution of PM 2.5 at the commune level, the new SPF model could be an excellent tool to check the consistency of the “pollution hypothesis” at any geographical scale. In particular, while the North/South gradient of particles coincides fairly well with the life expectancy gradient, this is not the case for their East-West distribution. A validation of the model for areas of discrepancy between fine particle density and life expectancy would therefore be exciting. A missed opportunity (for now?), since the authors were content to use their model to spatialise mortalities to a finer level, calculated with parameters validated in different models.

The question here is not whether this figure of 48,000 deaths per year due to PM 2.5 is correct or not, since the report does not provide the necessary elements to judge that. No effort is made to distinguish the effect of PM 2.5 from an effect considered to be just as scientifically proven, that of diet. It is as if SPF were to do epidemiological studies on lung cancer, without adjusting the results according to tobacco consumption. So it is all proceeding as if chronic mortality due to PM 2.5 has become a dogma, which pollution specialists no longer even try to verify. Yet even the proponents of this hypothesis show that much remains to be clarified. At the same time, an article published in Nature estimated the deaths due to PM 2.5 and NOx [i] at 38,000 per annum worldwide, including 28,000 in the European Union… compared to the 48,000 for France alone, and PM 2.5 alone, calculated by SPF! Spot the mistake… or the mistakes?

Give a dog a bad name…

In summary, this figure of 48,000 deaths:

- Is the upper range of an interval whose lower range is… 11

- Comes from a purely theoretical statistical model:

- with an unusual methodological choice (relative risk chosen a priori by the authors, and not calculated from actual mortality data)

- whose authors do not present any element of comparison with the reality on the ground

- amounts to attributing to air pollution the entire difference in life expectancy which has long been recorded between the North and the South of France, and which is usually explained by diet: this is of course possible, but it deserves to be reasoned through (whereas this “slight detail” is not even mentioned in the SPF report)

None of this is really scientifically beyond the pale, but it does show that these famous 48,000 deaths are at this stage only a combination of bold hypotheses, which very much need to be proven. This report remains in the field of theoretical speculation, and not in the quantification of a phenomenon solidly demonstrated on the ground: a legitimate stance for researchers (provided they then move on to validating their hypotheses…), but rather more surprising for a health assessment agency, supposed to rely on methodologies which are proven… and validated at the international level! And it is precisely if it were to be applied internationally that the SPF model would demonstrate its full impact. We have seen that at the national level, this model estimates that fine particles are responsible for 9% of deaths throughout France, including rural areas. Out of curiosity, we would like to know what percentage of mortality this model would reach for a city like Beijing, incomparably more polluted than even the worst French cities: 80, 150%? Similarly, SPF states without turning a hair that the number of excess deaths caused by pollution would be 48,000 if you take as a reference the French regions without anthropogenic pollution, and 11 if we take as a reference the European threshold of 25 μg of PM2,5/m3of air. This means that the European standard underestimates the number of victims of pollution by a factor of more than 4000. Why not? But this would also deserve international validation, unless we assume that the French are a people particularly sensitive to pollution.

The most elementary scientific caution would therefore have suggested not publishing such a bold hypothesis, without providing comparisons with actual mortality data by commune, and without having tested its plausibility for countries other than France. But when a hypothesis suits the political concerns of the moment so well, it is sometimes difficult to wait…

Fig. 2: The French Public Health report, which published the figure of 48,000 victims of air pollution in France per annum, was published one month after an article in the prestigious journal Nature, which attempted the same assessment on a worldwide scale. The militant environmental press largely parroted both these two publications, without ever noting their obvious contradictions:

- On the one hand, an estimate of 38,000 victims each year from PM 2.5 fine particulate matter and nitrogen oxides, on a global scale, thus including the hundreds of millions of inhabitants of the metropolises of emerging countries

- On the other hand, an estimate of 48 000 victims for MP 2.5 alone, on the scale of the 66 million French population, with considerably lower levels of air pollution.

[i] http://invs.santepubliquefrance.fr//Publications-et-outils/Rapports-et-syntheses/Environnement-et-sante/2016/Impacts-de-l-exposition-chronique-aux-particules-fines-sur-la-mortalite-en-France-continentale-et-analyse-des-gains-en-sante-de-plusieurs-scenarios-de-reduction-de-la-pollution-atmospherique

[ii] http://invs.santepubliquefrance.fr//beh/2015/1-2/pdf/2015_1-2_3.pdf

[iii] : http://www.forumphyto.fr/2016/06/13/la-peche-aux-alphas-niveau-expert-quand-les-particules-fines-nous-enfument/

[iv] https://www.ined.fr/fichier/rte/General/Publications/Population/articles/2013/population-fr-2013-3-france-conjoncture-mortalite-departement.pdf

[i] NOx : Nitrogen oxides

This post is also available in: FR (FR)DE (DE)

Dear Mr Stoop,

Thank you for article.

There are frequently misunderstood or misleading information in the press for general public. It is a pity but communicating properly scientific facts seems a difficult exercise in most of the cases.

I have remarks related to your comparison about the two articles in Le Monde with the figures “38000” vs “48000”.

The worldwide premature death figures from air pollution can be easily found on the WHO website:

“Ambient air pollution alone caused some 4.2 million deaths in 2016, while household air pollution from cooking with polluting fuels and technologies caused an estimated 3.8 million deaths in the same period.”

Source: http://www.who.int/news-room/detail/02-05-2018-9-out-of-10-people-worldwide-breathe-polluted-air-but-more-countries-are-taking-action

The article in Nature and the first related article in Le Monde, only studied the impact of emissions from diesel vehicles in excess compared to “normal” emissions from the certification limits. So the 38000 premature deaths are only the impact for a fraction of the PM emissions from diesel vehicules. This explains the discrepancies between the two figures.

I hope you will find it useful.

Dear Mr d’Haese

Thank you for your comment. You’re right, these discrepancies between both studies have scientific and logical explanations. Of course, the medias who reported these figures did not even try to understand the cause of these apparent contradictions, but one cannot blame only them.

The real problem is that premature death figures have strictly no sense in themselves, because they depend to much of the particules concentrations used as baseline reference. The only scientific interest of SPF’s study is to reveal clearly the absurd width of the uncertainty range resulting from the choice of this baseline (“from 48 000 to 11”).

As I pointed out in my article, long-term sanitary effects of air pollution cannot be measured directly, they can only be deduced from sophisticated statistical models, which may be affected by many confusing factors. I mentioned in my paper the most obvious of them in France, other confusing factors might also exist in other countries. Unless we consider that human sensitivity to air pollution depends of the country (a plausible but questionable hypothesis), the first and necessary step would be to examine the consistency of worldwide studies in this domain, to define a consensus value of the risk factor that can be realistically applied worldwide to each air pollutant, and the threshold values above which we may expect long-term effects. Then (but only then), it becomes possible to estimate a plausible figure for premature deathes. This is not the approach of Santé Publique France, whose study rely on a risk factor arbitrarily chosen by the authors, and whose lowest baseline for 2,5PM concentration obviously implies strong geographical and sociological biaises.

Dear Mr Stoop,

Many thanks for your very comprehensive article. I work with the Motorcycle Action Group (MAG) – in the UK. We have been concerned about the policy changes which are being made on the basis of unscientific claims about emissions. We in the UK (myself and a colleague) have identified very similar problems with claims about deaths from ambient air ‘pollution’ – PMs and NOx I particular – in the UK, and in some other international reports. In some cases, it is now claimed that 1 in 6 dearths in the UK is caused by air pollution. We believe that the desire to ‘prove’ the negative effect of ambient air pollution has resulted in a totally unacceptable rejection of all normal scientific methodology. We would like to discuss these matters further with your to compare our findings with yours. Would this be possible?

#1 Always ask if a news story is fact or PR

… PR tricks like darken graphics are an indication that it is PR

#2 Raw deaths is a BS measure,

.. cos are you talking about people who are dying at 82 an 2 days , instead of 82 and 32 days ?

A standard metric is QUALDs Quality Adjusted Life Days Lost

.. cos then you can calculate if it worth spending public money on

typo QALDs Quality Adjusted Life Days ..lost

Your typo “PM 2.5 particles (particles with a radius less than or equal to 2.5 mm) ”

NOT mm it’s 2.5 micrometres .. 2.5µm

============

I’ll mention a complexity

They probably assume all such particles are the same

And in many situations they will be a very similar variety of elements

But actually in other situations the actual material could be quite different in toxicity.

You’re right, we already corrected this typo in French, but not in English !

Thank you for a most informative and well researched article. As a non-scientist (though my working life was concerned with environmental management), I am curious to know if studies such as these take account of the fact that certain individuals are, unfortunately, more likely to suffer from the effects of “modern life” due to congenital conditions such as asthma or heart disease?

It strikes me that a fair analysis of the effects of particle additions to the atmosphere resulting from human activities could only be considered helpful (in terms of better environmental management), if there is a degree of acceptance that small numbers within any sample study are more prone to the effects than the larger population as a whole. For such individuals, the impact of entirely naturally arising air content can be quite as devastating as anthropological contributions.

This raises the wider issue of the cost / return relationship between “modern life” and its effects. By common reckoning, life expectancy (both at birth and in terms of longevity), general health, working conditions, and fair access to resources have all improved for citizens of developed nations since the advent of the industrial revolution. For peoples living in less developed countries, freedom from hunger and levels of survival have dramatically improved since the “green revolution”. Meaningful analysis of the standards of living in an advanced economy, therefore, must necessarily balance the benefits with the costs, an analysis that, by any reasoned account, weighs heavily to the favour of the benefits.