Today, 6 October 2023, 50 years ago, the Yom Kippur War began between Israel and the Arab countries. It lasted only a few days, but it was used as a pretext to revolutionise the oil market, as Arab countries decided to punish Western countries that supported Israel. The first oil crisis had far-reaching consequences. We will analyse the situation that led to the Arab countries to revolt against an unfair situation, since the beneficiaries of their production were the Western countries. We will see how the European Commission organised itself to withstand this shock. But the most interesting thing is the parallel with the current situation which, if it continues, would lead to a new oil crisis.

Seven sisters for the good of the West … and theirs too

When Western countries realised the strategic importance of oil at the end of the First World War, it was a development as extraordinary as digitalisation today. The bankers of the day understood that oil would revolutionise mobility – a basic human need – so they invested heavily and the oil industry flourished. Big oil companies were born and developed, just like GAFA today. They became so powerful that the ‘Seven Sisters’ formed a cartel. The Achnacarry Agreement (in the Scottish Highlands) established a method for setting the world price of oil and strengthened the position of the signatories by setting percentage increases for the future. It also streamlines the global oil industry to the benefit of consumers and producers, as other provisions establish product standardisation. As at present, both producers and consumers are winners, the latter because petroleum products radically improve their living conditions and make work less arduous. But the former are getting richer and investing more and more in innovation. The losers are undoubtedly the oil-producing countries, mainly east of the Suez, which receive only baksheesh for their crude oil.

The Second World War confirmed the crucial importance of what would become black gold. At the end of the war, the oil companies continued to dominate the oil world in the free world, with the support of the United Kingdom and the United States. Attempts were made to reverse the situation. In Iran in 1951, the government of Dr Mohammad Mossadegh nationalised oil, but Iran had to back down. In 1956, a skirmish over the Suez Canal caused a crisis that lasted only a few days.

In the 1960s, Enrico Mattei, the Italian president of Agip (now ENI), tried to persuade oil-producing countries to accept a ‘fifty-fifty’ deal, but he died in a plane crash before he could implement his project. Mattei had the genius to understand before anyone else that the world of oil was going to be taken over by governments. As this resource became so important for the economic development of the whole world, not just Western countries, the oil-producing states could no longer be content with the crumbs that fell from the table of the seven sisters. They will have to negotiate with the owners of the reserves and give them half of the revenues!

The situation before 1973

With the outbreak of the Six-Day War in 1967, oil gradually became a key political weapon in the third Arab-Israeli conflict. In 1968, the countries of the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), founded in 1960, declared for the first time their intention to nationalise their oil wells before the scheduled expiry of their concessions (often until the end of the century), thus removing them from the control of the Anglo-Saxon oil companies. In 1970, the dominance of the big companies began to waver.

However, there is no need to panic, as new hydrocarbon deposits were discovered in Nigeria, Libya and Malaysia in the 1960s. In the Netherlands, natural gas was discovered in Groningen, where production ceased on 1 October 2023. In particular, oil and gas have been discovered in the North Sea, including the large Norwegian Ekofisk field. Few Member States of the European Community (as the EU was then called) had an oil policy, despite the huge sums of money and efforts that all European countries had invested in coal (the subject of the ECSC Treaty) and nuclear energy (the subject of the Euratom Treaty).

Through their representatives in OPEC, the seizure of power by Colonel Muammar Gaddafi in Libya and the Shah of Iran, and the ‘agreements’ imposed on the major companies in Tehran in January 1971 and Tripoli in March 1971, the producing countries succeeded in shifting the balance of power. They now set the prices and quantities produced. They were in a strong position to negotiate the conditions for acquiring a majority stake in the operating companies within increasingly tight deadlines, and they threatened or carried out nationalisations (Iraq, Algeria).

The Club of Rome models have got us into all kinds of trouble!

In 1972, the Club of Rome published the ‘Meadows Report’ (written by a father and daughter) ‘The Limits to Growth’. With 30 million copies printed and translated into thirty languages, this book shaped a generation. Based on models (it was the beginning of computers), it predicted that oil reserves would run out by the year 2000. Everyone believed it, including me, which enabled me to do a PhD in the field. This report ‘to’ the Club of Rome is still praised by the degrowth movement, even though all its predictions have turned out to be wrong. Even Ursula von der Leyen told the European Parliament on 15 May that the Club of Rome had warned us to stop economic and demographic growth…

The Libyan Colonel Muammar Gaddafi rejoiced in the fear of the end of oil in 2000. Three years earlier, on 1 September 1969, he and Marshal Haftar, who now controls part of Libya, had overthrown King Idriss of Libya. Once in power, the young colonel nationalised the oil industry and created the National Oil Corporation. The unfair tax regime he imposed on foreign companies did not encourage major American companies to stay in the country. Today, as in the past, the first condition for producing oil is stability in the country, but in Gaddafi’s Libya the opposite is true. Libyan production is falling and has never returned to its pre-1969 level of 3.5 million barrels a day. The revolution has run out of cash. Oil prices need to rise to consolidate the power of the new regime.

Since the useful idiots believe the catastrophist models of the Club of Rome, the Colonel will exploit the fear of the end of oil and convince others to follow him in order to drive up the price of crude oil. The Club of Rome gave the Arab-Muslim countries a powerful weapon by making them believe, on the basis of models that turned out to be false, that the end of oil was near. It was the perfect opportunity for the OPEC countries, under the impetus of the Libyan colonel, to use their reserves to influence Western policy towards Israel.

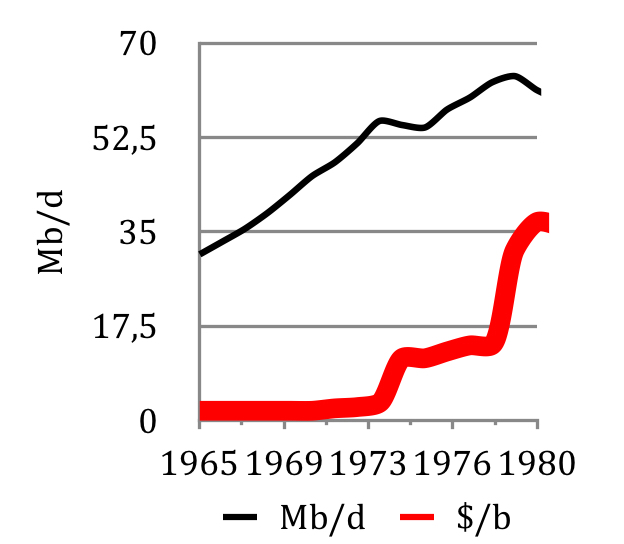

Yom Kippur War triggers the first oil shock

On 6 October 1973, the Jewish holiday of Yom Kippur, while the whole of Israel was celebrating the ‘Great Pardon’, Egypt and Syria attacked Israel to force it to return to the territories conquered in the 1967 Six-Day War. The price of oil skyrocketed. To force the Western countries to put pressure on Israel, the Arab oil-producing countries, OPAEC (not OPEC), meeting in Kuwait City ten days after the start of the war, raised the price by 70% and reduced the rate of oil exports to Europe and America by 5%. Supported by the Soviets – the Communists never miss an opportunity to oppose freedom – the Arab countries of OPEC caused the price of crude oil to soar, triggering a global energy crisis that is still being felt today. They set the price of oil at 5.75 dollars a barrel, compared with 3 dollars the day before…

But OPEC’s oil production is essential to balance the world’s demand for oil. Oil has become a political weapon in the international struggle against Israel and its allies. Production is cut by 5% a month and embargoes are imposed on countries deemed unfriendly and directly dependent on the outside world for almost two thirds of their imports: the United States, the Netherlands, Portugal and South Africa ‘until Israel has completely withdrawn from the Arab territories occupied in 1967 and the Palestinian people have been restored to their rights’.

At the end of the conflict on 23 October, OPEC cut its production by 25%. The consequences were immediate. On 25 December 1973 (!), at a meeting in Tehran, the Shah of Iran announced that the compromise between Saudi Arabia’s position of $7.5/b and that of the other OPEC members, who wanted $14.5/b, was $11.7/b. It should therefore be noted that Saudi Arabia is defending a minimalist position, a consequence of the Quincy Pact sealed between Saudi King Ibn Saud and US President Franklin Roosevelt on 14 February 1945, on Roosevelt’s return from Yalta in the Crimea, where he had taken part in the post-World War II ‘division of the world’..

OAPEC punishes with oil…

At the end of the meeting of OAPEC ministers in Kuwait on 25 December 1973, they bluntly announced that the rise in oil prices was intended to punish Israel.

‘The Minister’s meeting took into consideration the real objective of the oil measures which they had adopted, which was to make international opinion aware, without permitting the economic collapse which could affect one or more peoples in the world, of the unjust situation of the Arab nation as a result of the occupation of its territories and the expulsion of an entire Arab people, the Palestinian people. They wished to reaffirm once again what they have been saying since 17 October about the measures taken, which should in no way affect friendly countries, thus drawing a very clear distinction between those who support the Arabs, those who support the enemy and those who observe a neutral position…’

The aftermath of the 1973 crisis

OPEC found the secret of driving up the price of oil: simply turn off the Gulf spigot to drive up prices and try to influence political decisions.

The most tangible signs of the consequences of this first oil shock, which triggered the economic crisis, were a worrying rise in inflation and a global economic recession. The recycling of petrodollars partially offset these drawbacks. Energy spending accelerated the economic crisis that hit the EU, first in the form of a recession that abruptly ended the economic growth of the post-war boom. Industrial production fell, traditional sectors such as textiles, shipbuilding and steel were directly affected and bankruptcies multiplied. Developing countries had to go into debt in order to avoid the stagnation of development that had set in after decolonisation. They are still paying a heavy price today.

Much more than Mattei expected, the OPEC countries have taken control of the prices and quantities of oil produced. Before the crisis, 80% of oil was produced by private companies and only 20% by national companies. The way is clear for further increases, which are not far off.

It looks like 2023!

The EU organises itself to withstand the shock

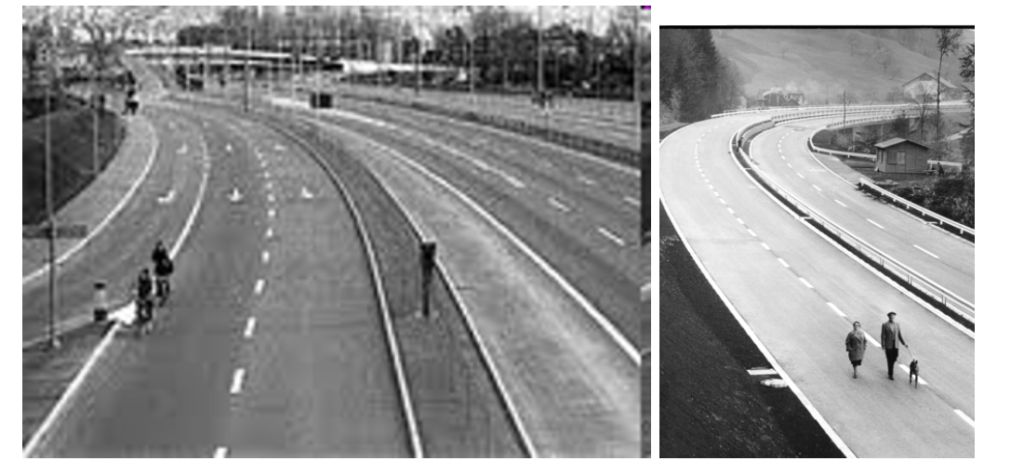

But the reaction was not long in coming. The consumer countries organised themselves and quickly created the International Energy Agency, a success of Henri Kissinger and the Belgian Étienne Davignon when he was at the OECD. States also reacted to reduce – ration – the consumption of petroleum products by declaring the famous car-free Sundays, the first of which took place on 18 November 1973. First it was for everyone, then it was for odd and even number plates. We began to talk about rational use of energy, and the slogan ‘In France, we have no oil, but we have ideas’. Energy management became a major public issue, long before man-made climate change. They also revived the old idea of winter time from the 1930s, which then had an agricultural objective; this time it was in the hope of using less energy for lighting, but in practice it turned out that the result was insignificant.

These circumstances have led to an intensification of oil exploration, with fierce competition for new oil concessions around the world. At the same time, the cost of exploration has risen sharply with the emergence of service companies (oil and gas sector) that perform a variety of tasks (seismic, drilling, supply vessels, etc.). Despite this increase in the price of exploration, a major exploration campaign has been launched in many countries by both traditional and non-traditional producers. Across Europe, including the North Sea, but also in Argentina, Chile, Bolivia, Brazil, Colombia and Malaysia, drilling is multiplying and discoveries are continuing. In the United States alone, there are some 4,000 drilling rigs in operation. All this, of course, is accompanied by a sharp increase in the number of people involved in this activity.

At the same time, we are witnessing the search for alternatives to oil: ethanol from sugar cane in Brazil, the production of gasoline from the large Maui methane deposit in New Zealand, but also the conversion of coal into liquid or gaseous hydrocarbons; it is in this last area that I wrote my doctoral thesis, funded by the European Commission, which has been at the forefront of all these activities in order not to succumb to OPEC’s stranglehold on oil. But the area that has responded best to the threats from certain producing countries is North Sea production. The Commission’s Oil and Gas Demonstration Programme for technological development has made North Sea production possible (I devote several pages to this success story in my book Energy insecurity: The organised destruction of the EU’s competitiveness). This initiative made it possible to succeed in the oil shock of the mid-1980s by bringing oil prices back to reasonable levels, both for producing countries and for Western consumers. The ecologists in the European Parliament were quick to kill this programme as soon as they came to power in Brussels-Strasbourg.

The oil counter-shock has had serious consequences for oil-producing countries. No one can control the global market. We are all interdependent, much more so today than fifty years ago. Vladimir Putin should remember that. So should Joe Biden. But what is most disappointing is that the EU team of Ursula von der Leyen and Frans Timmermans, with the help of their chief of staff Diederik Samson (a member of Greenpeace), have forged a Green Deal that contradicts everything we have learned in fifty years. Unless this Green Deal is radically reformed by the next European Parliament, which will be elected on 9 June, OPEC will return more powerful than it was fifty years ago.

In 1979, the second oil shock was worse, this time because of the strategic error of Jimmy Carter and Valéry Giscard d’Estaing, who wanted to overthrow the Shah of Iran, Reza Pahlevi, and replace him with Ayatollah Khomeini, who hastened to create an Islamic state and drive out the West. But we will talk about it again in six years’ time, on the fiftieth anniversary of the second oil shock.2023 like 1973?

What can we learn from the oil crisis? Firstly, do not believe the models: a computer cannot predict the future. Why define punitive and radical policies on the basis of these projections, even if the scientists want you to believe them? Think of the models that predict the temperature in 2100. They have been proven wrong so far, but many people – fewer and fewer – continue to believe them and are pushing the EU to adopt a policy of voluntary or involuntary decarbonisation (the subject of my latest book, mentioned above). At university I know well, there are plans to penalise researchers who travel to share their work and exchange ideas with other researchers. Research has always worked this way, but based on the IPCC models, research must now stop travelling in order to decarbonise.

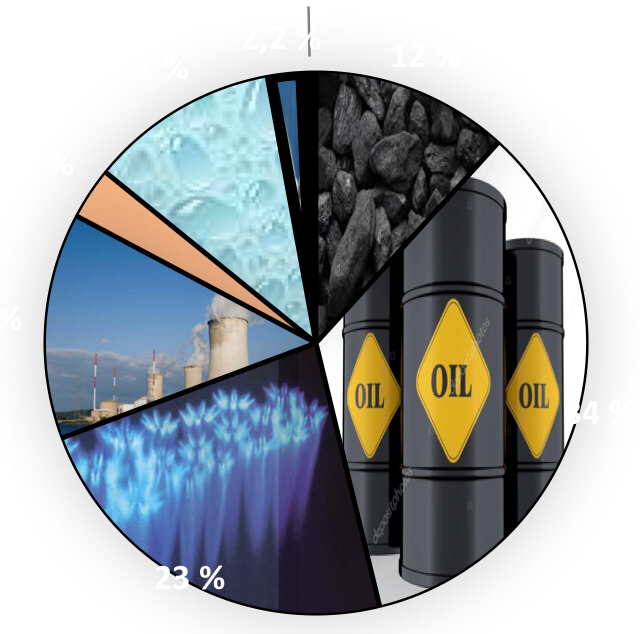

Secondly, technological research must continue, including in the field of hydrocarbons, which will remain unavoidable because – after 44 years of multiple subsidies and support – the primary energy produced by wind turbines and photovoltaic solar panels represents only 3% of the total and will not be able to approach 100% either in 2050 or later; to pretend otherwise is as implausible as saying that the oil companies have plans for a water engine in their drawer. It was the new technologies of the day – hydrocarbon extraction and nuclear power – that silenced the geopolitics of fear. There is no need to despair of the ability of engineers to find solutions to the problems we will continue to face.

More worryingly, EU banks are reluctant to finance conventional energy projects for fear of incurring the wrath of environmental NGOs. They are reducing or even stopping funding for projects that are vital for the future, as is the case with BNP and Société Générale, which like to show off their green credentials. On the other hand, banks outside the EU are investing heavily in the vital oil and gas sectors because they are not subject to the scrutiny of environmental NGOs.

If Brussels-Strasbourg does not change its position after the elections on 9 June 2024, we will fall into a trap similar to that of 1973. We did not know then that the Club of Rome was wrong. Today we do. There are enough energy experts to say that decarbonisation is a red herring. It is time to act if we want to avoid a shock, but this time it will not be global as in 1973, but confined to the green EU. And this shock will be far more severe than the one 50 years ago, as the rest of the world, encouraged by the BRICS+, rushes enthusiastically into conventional energy.

“Oil is ninety per cent politics” said the Belgian Henri Simonet in 1973, when he was European Commissioner for Energy. That was true then. It is still true, but the technological revolution that has taken place since then, and not just with shale oil and gas, means that many countries now have abundant reserves and can look to the future with more confidence than in the past, at least outside the EU. But politics remains important, as shown by the current European Commission’s aversion to oil and nuclear energy (although the latter is improving), which is in stark contrast to the European Commissioners of 1973. As far as I’m concerned, fifty years on, “oil is 50% politics, the rest is technology”.

By David Falconer, Photographer – This tag does not indicate the copyright status of the attached work. A normal copyright tag is still required. See Commons:Licensing., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3575687