On April 29, 2021, the European Commission (EC) opened the debate on the regulatory status of New Genomic Techniques (NGTs) in the European Union (EU) by publishing a position paper[1]. Using this concept of NGTs, it indicates that this study is not just about plants (even it is actually almost exclusively focused on them) but also concerns microorganisms and animals that will be treated later. We welcome the renewal of a policy that becomes now open to biotechnological innovation in order to improve sustainability.

This openness sweeps away the judgment of the European Court of Justice of July 25, 2018, which indicated that all products resulting from NGTs subsequent to 2001, particularly NGTs applied to plant varietal selection (also called NBTs for New Breeding Techniques), were to be considered and regulated as GMOs. This heavy European regulation for GMOs practically prevented their development in most countries of EU[2]. However, can the EU stand aside and ignore them, in a world where a majority of countries have now opened up, with varying degrees, to NGTs? Among these NGTs, is of particular notice the flagship technique CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats) published in 2012 in Science by Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer Doudna who were rewarded for this discovery with the attribution of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2020. CRISPR described as “molecular scissors” is considered to be a real technological breakthrough. The focus is here on geopolitics. Would the Member States be able to preserve the UE agrifood independence if access to biotechnological innovations were refused to them because of an obsolete regulation rejecting the advancement of scientific knowledge? Would they be able to feed the European population and provide with their needs in complete sovereignty?

A Regulatory Cleavage

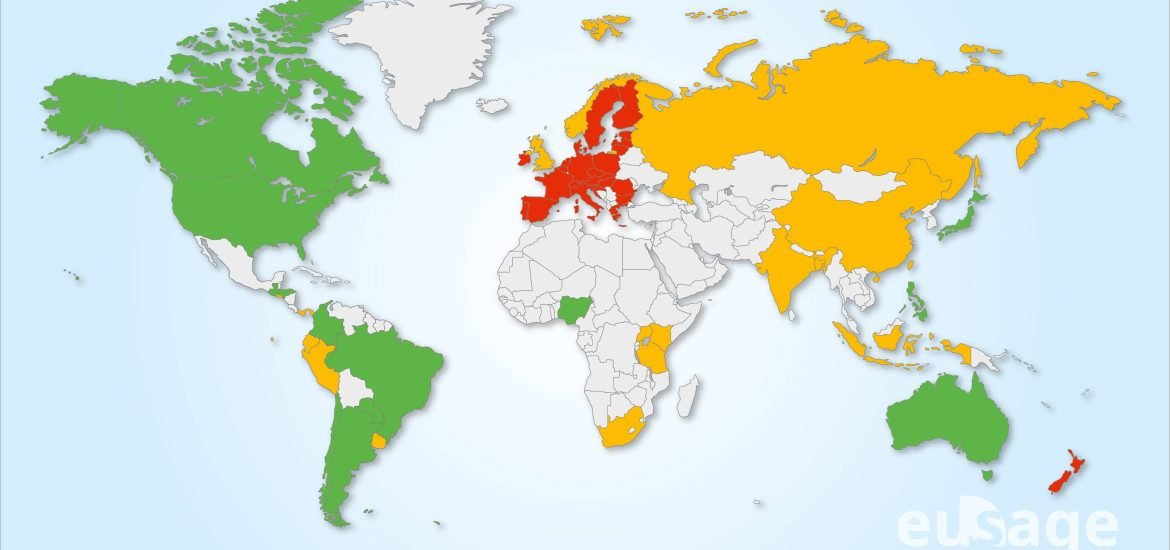

The world is now divided between probiotech countries (which cultivate and import / export GMO crops) and those who express more reservations (which import GMO crops but refuse cultivation like France); on one side: the American and Asian continents, the Pacific-Oceania zone, on the other: the Middle East, Russia, a majority of African countries and European countries except Spain and Portugal. This cleavage is now also found in the reception that has been reserved for NGT products. This acceptability of NGTs is measured by the regulations applied to them in each individual country. Today, the probiotech countries have decided to exempt most products obtained by NBTs from the regulations applied to GMOs while many other countries are leading discussions to determine the level of exemption to be granted to NGT products. On a map published recently by Dima and Inzé[3], countries favorable to NBTs are colored in green, countries whose reflection is in progress or which choose intermediate regulatory positions are in orange while those which have adopted restrictive regulations by assimilating NBT products to GMOs are in red. Only New Zealand and the EU were to be found in this category until last March 2021. However New Zealand’s position is currently evolving as well as EU after its recent release of April 29, 2021.

Towards Global Regulatory Relief for NGTs Minor Genomic Modifications

Land of choice for biotech plants for more than 20 years, the countries of South America were the first to adopt specific regulations for NGTs: Argentina in the lead in 2015, followed by Chile in 2017, Colombia and Brazil in 2018, then Paraguay in 2019. These countries have decided to carry out case-by-case evaluations of the NGT products and to exempt from GMO regulation any new genetically modified organism that would not have “new combinations of genetic material” [4]: those which do not incorporate foreign DNA are not considered to be GMOs. In the United States, new rules, called SECURE (Sustainable, Ecological, Consistent, Uniform, Responsible and Efficient) Rule applied to new Genome Editing biotechnologies, were published on May 18, 2020 after extensive consultation to collect everyone’s opinion. A plant genetically edited for minor genome modifications such as the change or removal of a base pair or the introduction of a gene known to belong to the genetic pool of the plant will be exempted from federal regulations applied to GMOs[5]. It is the characteristics of the final product that are now evaluated and not the method of production. According to APHIS-USDA, more than 98% of new varieties submitted for marketing authorization will benefit from this regulatory relief. Another North American country, Canada treats NGT products like other innovative products with novel traits. The properties of the resulting finished product are assessed on a case-by-case basis by the CFIA (Canadian Food Inspection Agency).

On other continents, Japan and Israel have decided to deregulate genetic products that do not contain new foreign DNA. Australia exempts from regulation products with minor genome modifications. Russia reaffirmed in 2020 its opposition to the cultivation and breeding of agricultural GMOs except for research purposes. But since 2019 it has been developing a research program worth 111 billion rubles (about 1.23 billion euros) to develop around thirty genetically edited (NBT) varieties of wheat, barley, sugar beets and potatoes, these new varieties being considered as equivalent to varieties obtained in a conventional manner[6]. China has not defined a specific regulatory status for genome editing products but has initiated research programs worth US $ 10 billion. This country leads the highest number of patents for agricultural applications of CRISPR[7]. Several countries in Southeastern Asia are also continuing their assessments.

What are the consequences of these regulatory adjustments? The Argentinians early chose for a lighter regulation. They now experience a reduction in approval costs which is accompanied by an expanded offer of new NBT products. This favors the development of new and more efficient varieties to adapt them to climate change or better resist pathogens and insect pests from crops.

Evolution of New Zealand and the European Union’s Policy

The New Zealand government following a ruling from its High Court of Justice in 2016 decided that genome editing products should be considered GMOs. But ensuing discussions led by the Royal Society of New Zealand in the years that followed, the status of NBT products without foreign DNA is now studied to be exempted from GMO regulation[8].

And now it’s the EU’s turn to reconsider its regulatory position. EC observes the gap that is growing day by day between Europe and the countries that have widely adopted NGTs with appropriate regulations. It thus notes that regulating NGT products as GMOs introduces a distortion of competition in international trade, which would penalize economy of Member States and also affect European research, public and private as well. EC also emphasizes that it is difficult to differentiate NBT products which do not contain foreign DNA, for example those resulting from targeted mutagenesis or cisgenesis. It indicates that many products obtained from the New Genomic Techniques would be strongly involve in the “European Green Deal” and the “Farm to Fork Strategy”. Consequently, Portugal, which is now presiding EU, has been asked to conduct a debate in order to modify the regulation so that it will take into account the sustainable protection of health and the environment without neglecting the opportunities offered by new genomic technological innovations[9]. It should be noted that Portugal is one of two EU Member States that still cultivate GMOs (MON 810 maize, resistant to the corn borer and sesamia, major insect pests of the crop which covers 5,733 hectares in 2018 in Portugal). In this country, biotech, organic and conventional agricultures coexist harmoniously in the regions of Lisbon and Alentejo through appropriate legislation[10].

To the Reconquest of Agrifood Sovereignty

In a globalized world, can a country adopt a position hostile to new genomic technologies? Even though it is not scientifically possible to ultimately distinguish between products resulting from natural mutation or from in vitro or in vivo directed mutation, as the French High Council for Biotechnologies has pointed out[11] ? The French Minister of Agriculture Julien Denormandie recently concluded on May 6, 2021 at the meeting of the French Seed Union (UFS) on the critical place occupied by the seed sector in the French economy. With MP Jean-Baptiste Moreau (himself a farmer) who chaired these exchanges, he underlined the strategic interest of implementing varietal improvements by NBTs and so “reconquer our food sovereignty”. France will preside EU in January 2022. His position encourages for a smart revision of the European regulation on NGTs which is a key for our EU future. The responsibility of French presidency will be therefore involved in an historical and huge challenge.

Expecting that this EC study on NGTs, at this moment mainly focused on NBTs, will soon be extended to microorganisms and animals, we must today support the new realistic position of the European Commission, which will enable the Union to face the challenges of the future with appropriate biotechnological tools.

[1] European Commission (2021) EC study on new genomic techniques Brussels, 29.4.2021 SWD(2021) 92 final, https://ec.europa.eu/food/plant/gmo/modern_biotech/new-genomic-techniques_en

[2] Catherine Regnault-Roger (2018). La réglementation au cœur des débats, In Au-delà des OGM, Regnault-Roger C. et al (Dir), Presses des Mines, pp135-168

[3] Dima Oana. & Inzé Dirk (2021), The role of scientists in policy making for more sustainable agriculture Current Biology, 31, R219-220, March 2021 & Regnault-Roger Catherine (2021) Regulatory and politicial challenges of New Breeding Techniques, European Seeds 8 (2) : 30-33 (Map reproduction , courtesy EU-SAGE)

[4] Sarah M Schmidt, Melinda Belisle & Wolf B Frommer(2020) The evolving landscape around genome

editing in agriculture, EMBO Reports (2020) 21: e50680 | Published online 19 May 2020

[5] Bernadette Juarez (2020) Sustainable, Ecological, Consistent, Uniform, Responsible and Efficient (SECURE Rule) Overview, USDA, https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/ourfocus/biotechnology/biotech-rule-revision

[6] Global gene editing regulation tracker, Human and Agriculture Gene Editing Regulations et Index https://crispr-gene-editing-regs-tracker.geneticliteracyproject.org/ ( in line l6.0. 2021)

[7] Catherine Regnault-Roger (2020) OGM et produits d’édition du génome : enjeux réglementaires et géopolitiques Fondation pour l’innovation politique, janvier 2020, 56 pages

[8] Global gene editing regulation tracker, Human and Agriculture Gene Editing Regulations et Index https://crispr-gene-editing-regs-tracker.geneticliteracyproject.org/ ( in line l6.0. 2021)

[9] EC study on new genomic techniques Brussels, 29.4.2021 SWD(2021) 92 final .Letter to the Portuguese Presidency https://ec.europa.eu/food/plant/gmo/modern_biotech/new-genomic-techniques_en

[10] Catherine Regnault-Roger (2020) Des plantes biotech au service de la santé du végétal et de l’environnement, Fondation pour l’innovation politique, janvier 2020, 56 pages

[11] Avis du HCB sur le projet de décret modifiant l’article D.531-2 du code de l’environnement, http://www.hautconseildesbiotechnologies.fr/sites/www.hautconseildesbiotechnologies.fr/files/file_fields/2020/12/11/avis-cs-hcb-projet-decret-modifiant-code-environnement-200707-rev-201203.pdf (en ligne le 9/01/2021)

Read further on the same topics

The European Commission publishes its study on New Genomic Techniques

European Citizens’ Initiative: sign the Green Biotech Petition

This post is also available in: FR (FR)

If France gets to preside the EU for 6 months starting in January, knowing that there is a presidential election in May, I am afraid the president will do nothing on this controversial topic…