The theory of Anthropogenic Global Warming is regularly presented as benefiting from a solid scientific consensus. What proves the solidity of this consensus? A scientific article, published in 2016 by Cook and colleagues, proposed a synthesis of the work: from the examination of studies available at that time, the authors showed that the consensus on the reality of climate change was shared by 90%-100% of scientific climate experts. An estimate that we find widely relayed in the media today. In 2019, Powell said he found consensus to be 100%. In this article, we propose to analyze the potential biases in the work of Cook and colleagues, in order to understand how these biases could affect the claimed level of consensus. We also deal with Powell’s recent assert of 100% consensus and enlighten potential cognitive & methodological biases in his approach.

An undeniable consensus?

In their 2016 paper consensus on consensus: a synthesis of consensus estimates on human-caused global warming [1] , Cook and colleagues argued that “the consensus that humans are causing recent global warming is shared by 90%–100% of publishing climate scientists according to six independent studies by co-authors of this paper” and that those results were consistent with the 97% consensus reported by Cook and (other) colleagues 3 years earlier [2] in 2013. These values on consensus seem widely accepted today. However, some nuance can be brought regarding the validity of the methodologies used to reach these consensus levels. We list and detail below some fundamental biases or logical fallacies we found in the demonstrations, and their possible consequences.

Logical fallacy

In 2013, Cook and colleagues [2] analyzed 11 944 papers written by 29 083 authors and published in 1980 scientific journals. They claimed a 97% consensus. How was this 97% consensus built? 97.1% is the percentage of papers that endorse AGW(1) among papers that express a position on AGW. But, among the 11944 papers, only 33,6% , i.e 4014 papers express a position on AGW. So, strictly speaking, AGW is endorsed by 97,1% of the 4014 selected papers expressing a position on AGW , i.e 3898 papers i.e 32,6% of all selected papers.

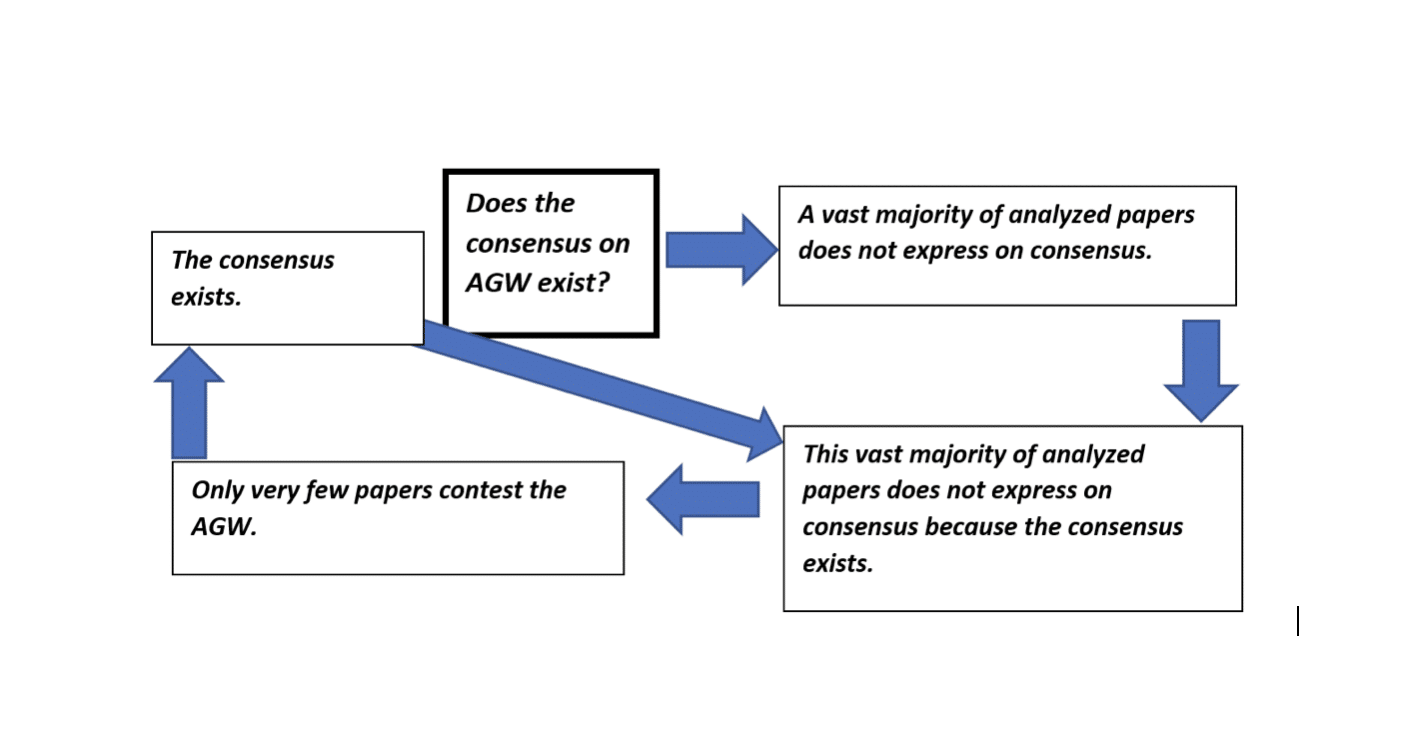

What about the 66.4% (7930) remaining selected papers? According to Cook’s analysis, they do not express any position on AGW. To explain such a fact, Cook and colleagues argue the following: “this result is expected in consensus situations where scientists generally focus their discussions on questions that are still disputed or unanswered rather than on matters about which everyone agrees. This explanation is also consistent with a description of consensus as a ‘spiral trajectory’ in which ‘initially intense contestation generates rapid settlement and induces a spiral of new questions’ ; the fundamental science of AGW is no longer controversial among the publishing science community and the remaining debate in the field has moved to other topics. This is supported by the fact that more than half of the self-rated endorsement papers did not express a position on AGW in their abstracts”. A skeptical approach must be used as we found a logical fallacy in the previous explanation: among the two main groups of papers, according to Cook’s classification, one expresses a position on (and mainly in favor of) the consensus (33,6%), the other does not express any position on the consensus (66,4%). When Cook and colleagues explain that the lack of expression on consensus by 66,4% of selected papers is a consequence of the consensus, they are entering a circular reasoning (figure 1): they consider the fact that a consensus does exist can explain that a majority of papers does not express any position on the consensus, what permits to conclude there is no rejection of the consensus, and that a consensus does exist. By doing this way they refer to the expected result into the demonstration of the result.

The relevancy of some references to arguments from a book chapter [3] written by Oreskes, one of the co-authors of the 2016 Cook’s paper, must also be questioned for similar reasons. Indeed, Oreskes precise in her book chapter, to explain why a vast majority of published papers does not express a position on AGW, that “the authors evidently accept the premise that climate change is real and want to track, evaluate, and understand its impacts“. Here again, the consensus is postulated to demonstrate the reality of this consensus.

We understand that a consensus could lead to a decrease in the intensity of a given debate but how can we accept the argument that a consensus does exist because there is a consensus? Such a circular reasoning is not acceptable. As Bertrand Russell said “the method of ‘postulating’ what we want has many advantages; they are the same as the advantages of theft over honest toil”.

Figure 1: circular reasoning used in Cook et al [2].

Confirmation bias

Rating method is a source of bias admitted by Cook and colleagues [2] who wrote that “subjectivity is inherent in the abstract rating process”. Such a rating bias is in fact a confirmation bias. Two sources of confirmation bias were cited: “first, given that the raters themselves endorsed the scientific consensus on AGW, they may have been more likely to classify papers as sharing that endorsement. Second, scientific reticence may have exerted an opposite effect by biasing raters towards a ‘no position’ classification.” Cook et al [2] tried to partially address this bias by using multiple independent raters and by comparing abstract rating results to author self-ratings. However, it was not enough: Cook and colleagues misclassified several papers, according to their authors [15]. We cannot exclude this error was duplicated to a significant number of papers.

Selection biases and sample size issues

Selection bias of papers and, consequently, representativeness of papers, is a potential issue that also could affect the evaluation of consensus on AGW as built by Cook and colleagues in their 2013 paper. Potential selection bias was addressed by collecting a large sample in literature. Nevertheless, 11 944 papers are only a fraction of the climate literature. Cook et al [2] outlined that “A Web of Science search for ‘climate change’ over the same period yields 43 548 papers, while a search for ‘climate’ yields 128 440 papers”. One cannot exclude the possibility that the frame was perhaps too small to catch the full variety of earth & climate scientists’ opinions.

Another way used in 2013 Cook’s study to evaluate consensus is the self-rating by authors of papers themselves. Cook’s team emailed 8547 authors and asked them to rate their own papers. Cook’s team received 1200 responses, i.e a 14% response rate, what allowed to get self-rating for 2142 papers from 1189(2) authors: among self-rated papers that stated a position on AGW (1381), 97.2% endorsed the consensus (1342). Among self-rated papers not expressing a position on AGW (761), 53.8% were self-rated as endorsing the consensus (409). Percentage seems significant and is effectively significant if the 14% response rate can be extrapolated to a wider sample. In other words, if the external validity of the measurement is good. But here again, there is the risk of a lack of external validity because of selection bias: it cannot be excluded that people who answered to the emails were mainly those motivated to make AGW recognized as a reality; and that other authors not interested in, or afraid by being seen as denialers, refused to answer. The only rigorous thing that could be said from this test is that AGW is endorsed by self-rating for 15% (1751/ 11944) of the total initial number of selected papers.

It is here interesting to note that among self-rated papers not expressing a position on AGW (761), 53.8% were self-rated as endorsing the consensus (409). Does it mean that 46,2% were self-rated as non-endorsing or rejecting the consensus? If yes, it could seriously undermine the statement of Cook’s team that a vast majority of all selected papers does not express position on AGW because the authors evidently endorse AGW.

Some other studies cited by Cook et al [1] in their 2016 synthesis suggest a high level of consensus on AGW(3). However, even if we make the probably false but conservative and optimistic assumption that there is no “authors” overlap among samples of each of these studies, the total number of scientists taking position for AGW trough these studies remains only a limited fraction of the climate scientists community. What poses again a clear risk for representativeness. For example:

Carlton et al (2015) [4] suggested a consensus as high as 96,7% for AGW among 306 biophysicists who had indicated that their researches concerned climate change or the impacts of climate change. It is however only one sixth of the almost 2000 scientists solicited for the study and represents, in proportion, 1 % of the 29083 authors that Cook and colleagues [2] identified as publishers in climate science.

Verheggen et al (2014) [5] surveyed 1868 scientists. 623 of them agreed with the fact that over half of global warming since the mid-20th century can be attributed to human-induced increases in atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations. It is around 90% of respondents who reported having authored more than 10 peer-reviewed climate-related publications, but only 10% of the 6550 climate scientists who were solicited for the study and it represents, in proportion, only 2 % of the 29083 authors that Cook and colleagues [2] identified as publishers in climate science.

Experimenter effect & social acceptability of results

For most of studies examined in Cook’s 2016 paper, evaluations of the level of consensus were made thanks to questionnaires sent to scientists, what makes evaluations sensitive to experimenter effect by which it can happen that responses are influenced by the subject’s perception of experimenter’s expectations. Typically, such a bias appears during face-to-face interviews. But even with non-face-to-face questionnaires one must verify the way the questions are formulated cannot influence the answer in favor of writer expectations. It would have been interesting to counterbalance such a kind of question “do you agree with the sentence: Humans are a contributing cause of global warming over the past 150 years ?” by such a kind of question “ do you agree with the sentence: Humans are not a contributing cause of global warming over the past 150 years ?” , between different groups, to evaluate potential effects on responses of experimenter’s expectations and formulation of questions. It is known by specialists of cognition that rates of positive and negative answers to symmetric questions is not equal.

Moreover, a common bias in survey responses is related to social acceptability: respondents are much more likely to endorse an affirmation when it is in line with social expectations. A preliminary socio-cognitive evaluation of the questionnaires on AGW endorsement should have been made and published to help readers understand how these risks of biases could affect the results or how they were removed.

Eventually, another major potential bias in consensus evaluation could come from how researches are financed and published. In her paper [13] cited by Cook and colleagues [2], Oreskes reminded us that the scientific consensus is clearly expressed in the reports of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. This agreement on the consensus is shared by US National Academy of Sciences, the American Meteorological Society, the American Geophysical Union, and the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS). Oreskes emitted the possible hypothesis that such an agreement on consensus expressed by scientific societies and academic communities could downplay dissenting opinions, and tested this hypothesis by analyzing 928 abstracts, published in refereed scientific journals between 1993 and 2003. These abstracts were listed in the ISI database with the keywords “climate change”. Oreskes claimed that 75% of the papers explicitly or implicitly accepted the consensus and the 25% remaining dealt with methods or paleoclimate, without any position on current alleged anthropogenic climate change. None of the papers were found to disagree with the consensus. Oreskes concluded that scientists publishing in peer-reviewed literature agreed with IPCC and professional societies and that impression of dissension between climate scientists was incorrect. However, the explanation could be different: one could assume also that only the results consistent with IPCC views are published in peer-reviewed literature. Oreskes did not consider this possible explanation and so her analysis cannot permit to decide between one of these two assertions: no published paper disagrees with IPCC views or papers that disagree with IPCC views are not published. An analysis of rejected abstracts should have been done to remove any doubt on a potential bias of publication, especially related to over-representation of some research authors: in another field, Locher and colleagues [14] analyzed 4 986 335 articles from 5 468 scientific journals specialized in infectious diseases selected from the National Library of Medicine between 2015 and 2019 and showed that in more than 60% of a sample of one hundred journals, the most publishing author is also member of the editorial staff, and is redactor in chief in 26% of cases. Can we without any doubt exclude some similar situation in the field of climate change with an over-representation of papers aligned with some views of editorial committees? Probably, no. Some researchers, as astrophysicist Nir Shaviv whose paper was misclassified by Cook et al [2], do explain that passing the refereeing step requires sometimes to not explicitly reject AGW. Nir Shaviv [15]:

“The paper shows that if cosmic rays are included in empirical climate sensitivity analyses, then one finds that different time scales consistently give a low climate sensitivity. i.e., it supports the idea that cosmic rays affect the climate and that climate sensitivity is low. This means that part of the 20th century should be attributed to the increased solar activity and that 21st century warming under a business as usual scenario should be low (about 1°C).

I couldn’t write these things more explicitly in the paper because of the refereeing, however, you don’t have to be a genius to reach these conclusions from the paper.“

As the subject of global warming has become an eminently political and social subject, we think that social acceptability of results could be one powerful driver of publication bias in climate science.

A 100% magic consensus

That said, another recent study claimed a full consensus (100%). This study was published by Powell [16] who used the Web of Science core database to search for peer-reviewed articles on “climate change” or “global warming” published in 2019: it represents 21 813 articles, for which he read the title for deciding if the articles might question AGW. If the title suggested that AGW was questioned by the article, Powell read the abstract and sometimes the full text, looking for a clear rejection. That’s a huge but insufficient work to claim a 100% consensus, because some typical biases or logical fallacies can undermine the results if not controlled or removed. Among these biases, the most important are:

-a selection bias, due to keywords. We cannot exclude that papers selection by the keywords used by Powell blinded him to some papers rejecting AGW.

-a confirmation bias, because Powell endorsed AGW and judged by him-self if a title was rejecting or endorsing AGW. Powell writes “it is inconceivable that any climate scientist today could have no opinion on the subject”[17]. Is it conceivable that Powell’s own opinion may have influenced the way he understood or classified the articles?

-a publication bias, that cannot be excluded and should be removed before claiming a very high level of consensus. An analysis of rejected papers should have been done. Moreover, contrary to what Powell says, his potentially biased analysis of peer-reviewed literature is not “incomparably better than merely asking scientists their opinion” [18] but is complementary because, even if interviewing scientists is a protocol requesting a good control of possible biases, it could permit to catch some non-peer reviewed expertise potentially hidden by the bias of publication.

-a circular reasoning. As Cook and colleagues do, Powell enters a circular reasoning with the consensus itself referring to the consensus: “it is a known and easily verifiable fact that publishing scientists rarely directly endorse the leading theory of their discipline. They take it as a given” [18]. It is probably true, but such an argument cannot be used to prove the consensus, because, as we said previously, it would force us to admit that a consensus exists because there is a consensus.

Consensus on global warming must be questioned by scientists

By examining several articles that suggest an extremely high level of consensus on Anthropogenic Global Warming, we have shown that this assessment is built on a significant but however limited fraction of available scientific publications or a limited number of explicit opinions. We have shown how some authors asserting an extremely high level of consensus on AGW had used of artificial circular reasoning to convince and we have pointed out that several method biases (especially confirmation biases, selection biases, publication biases, experimenter effect, social acceptability) did not seem under control. Because of these potential biases, 90-100% could be too optimistic evaluations of the current consensus on AGW.

Our conclusion about potential over-estimation of consensus on AGW does not mean that global warming due to human activities does not exist. But a claim of 100% consensus borders to magic unless it is upheld by a solid proof that we did not find to date in papers claiming it. It must be questioned. Questioning is not denying. It is a necessary tool for maintaining good hygiene in the practice of science.

The full climate science community should probably find a way to rigorously analyze its own work, with a verified unbiased methodology, to build scientifically the level of agreement on AGW and should avoid ill-founded magic claims that can attract public attention but pose the risk of discrediting science.

Probity requirements apply to all scientists, including climate scientists.

References

[1] John Cook, Naomi Oreskes, Peter T Doran, William R L Anderegg, Bart Verheggen, Ed W Maibach, J Stuart Carlton, Stephan Lewandowsky, Andrew G Skuce, Sarah A Green, Dana Nuccitelli, Peter Jacobs, Mark Richardson, Bärbel Winkler, Rob Painting and Ken Rice, Consensus on consensus: a synthesis of consensus estimates on human-caused global warming (2016) Environmental Research Letters, Volume 11, Number 4.

[2] John Cook, Dana Nuccitelli, Sarah A Green, Mark Richardson, Bärbel Winkler, Rob Painting, Robert Way, Peter Jacobs and Andrew Skuce, Quantifying the consensus on anthropogenic global warming in the scientific literature, Environmental Research Letters, Volume 8, Number 2.

[3] Oreskes N 2007 The scientific consensus on climate change: how do we know we’re not wrong? Climate Change: What It Means for Us, Our Children, and Our Grandchildren (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press)

[4] Carlton J S, Perry-Hill R, Huber M and Prokopy L S 2015 The climate change consensus extends beyond climate scientists Environ. Res. Lett. 10 094025

[5] Verheggen B, Strengers B, Cook J, van Dorland R, Vringer K, Peters J, Visser H and Meyer L 2014 Scientists’ views about attribution of global warming Environ. Sci. Technol. 48 8963–71

[6] Pew Research Center 2015 An elaboration of AAAS Scientists’ views (http://pewinternet.org/files/2015/07/Report-AAAS-Members-Elaboration_FINAL.pdf)

[7] Stenhouse N, Maibach E, Cobb S, Ban R, Bleistein A, Croft P, Bierly E, Seitter K, Rasmussen G and Leiserowitz A 2014 Meteorologists’ views about global warming: a survey of american meteorological society professional members Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 95 1029–40

[8] Rosenberg S, Vedlitz A, Cowman D F and Zahran S 2010 Climate change: a profile of US climate scientists’ perspectives Clim. Change 101 311–29

[9] Bray D 2010 The scientific consensus of climate change revisited Environmental Science & Policy 13 340–50

[10] Anderegg W R L, Prall J W, Harold J and Schneider S H 2010 Expert credibility in climate change Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107 12107–9

[11] Doran P and Zimmerman M 2009 Examining the scientific consensus on climate change Eos, Transactions American Geophysical Union 90 22

[12] Bray D and von Storch H 2007 (Geesthacht: GKSS) The Perspectives of Climate Scientists on Global Climate Change

[13] Oreskes N 2004 Beyond the ivory tower. The scientific consensus on climate change Science 306 1686

[14] Locher, C., Moher, D., Cristea, I., & Florian, N. (2020, July 15). Publication by association: the Covid-19 pandemic reveals relationships between authors and editors. https://doi.org/10.31222/osf.io/64u3s

[16] Powell J. Scientists Reach 100% Consensus on Anthropogenic Global Warming. Bulletin of Science, Technology & Society. 2019;37(4):183-184.

[17] James Powell is wrong about the 99.99% AGW consensus (skepticalscience.com)

[18] Method | James Lawrence Powell (jamespowell.org)

(1) Anthropogenic Global Warming

(2) Some responding authors of not peer-reviewed papers were removed from the study.

(3) Carlton et al (2015) [4] suggested a consensus as high as 96,7% for AGW among 306 biophysicists; Verheggen et al (2014) [5] surveyed 1868 scientists and claimed almost 90% consensus among respondents who reported having authored more than 10 peer-reviewed climate-related publications ; Researchers from Pew Research center [6], in 2015, suggested a 93% consensus for AGW among 132 working Earth scientists; Stenhouse et al (2014) [7] reached 93% of agreement on AGW among 124 AMS (American Meteorological Society) members who self-reported expertise in climate science; Rosenberg et al (2010) [8] reached a 88,5% consensus among 433 US climate scientists authoring articles in scientific journals that highlight climate change research; Bray (2010) [9] estimated a 83,5% consensus on 370 authors; Anderegg et al (2010)[10] reached a 97% consensus among the 200 most published authors (of climate-related papers); Doran and Zimmerman (2009) [11] reached a 97% consensus among 77 climatologists who were active publishers of climate research; Bray and von Storch reached a 40% consensus among 539scientists, then a 53% consensus among 530 scientists [12]; Oreskes (2004) [13] reached 100% among 928 peer-reviewed papers on global climate change.

Image par 愚木混株 Cdd20 de Pixabay

This post is also available in: FR (FR)