On 4 December 2019, in her first Brussels press conference the newly appointed president of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, said she will lead a ‘geopolitical Commission’. One year later, we are still waiting for some ‘geopolitical’ results. Indeed, it is rather a ‘green Commission’, as even the Covid crisis – though its cause is totally unrelated to energy – is used to reinforce the ‘energy transition’, wanted by the German Chancellor. In September 1999, arriving as president of the European Commission Mr Romano Prodi has been convinced that energy was not so important and that it did not deserve to be managed by an energy general directorate. It merged it with the transport energy directorate. What a difference twenty later: energy is now the centre of all interest, not for its own merits, but because it is at the centre of the climate change debate. But are politicians able to drive the vast, complex and multi-dependent energy system? Is their willingness’s able to master it effective?

Not surprisingly, this concept of ‘energy transition’ was invented in Germany in the early 1980s. In a book entitled ‘Energie-Wende, Wachstum und Wohlstand ohne Erdöl und Uran’ published in 1980, researchers from a German environmentalist organisation, the Öko-Institut, proposed to stop using oil and uranium. The simplified term ‘EnergieWende’ was quickly coined to refer to the fight against climate change and the abandonment of nuclear energy. Germany has firmly followed this track since the beginning of the 21st century, aiming at a radical change in its energy policy. The German population has also adhered to this concept because, after 40 years of green nuclear bashing, it has become widely opposed tonuclear energy.

The EnergieWende was progressively pushed, but the Fukushima Tsunami accident boosted its implementation. Mrs Merkel, a doctor in physics, won two elections by claiming that nuclear energy was essential for the German economy. Yet, after the hydrogen explosion[1] known as nuclear explosion, she made a U-turn and became an opponent of atomic energy, and turned out to be strongly convinced that the future of energy in the world would be 100% renewable. Massive investments promoted wind and solar renewable energy, despite the huge problems caused by their intermittency, leading to huge price increases for citizens.

[1] The explosion occurred due to an accumulation of hydrogen following a reaction of zirconium with too hot water. This accident can simply be avoided; all European reactors are equipped with a very simple static device (Passive autocatalytic recombiner – PAR).

The setback of the renewable energy policy

In 2005, during a German presidency of the EU, Mrs Merkel asked Mr José Manuel Barroso, president of the European Commission, to prepare a ‘road map’ in favour of renewable energy. The Commission published a Communication on 10 January 2007: ‘Renewable Energy Road Map. Renewable energies in the 21st century: building a more sustainable future’. This paved the way for a directive adopted in 2009. The latter set a mandatory target of 20% for renewable energy’s share in final energy consumption in the EU by 2020 and a mandatory minimum target of 10% for biofuels. It also set up a new legislative framework to enhance the promotion and use of renewable energy.

As we are nearing the end of 2020, we can start to analyse the impact of the directive and how the Members States have met their obligation, which they set for themselves. We see that most of the Members States are not on track for reaching their target, with a few exceptions (Sweden, Croatia, Estonia, Denmark, etc.). It is ironical to see that its promoter, Germany, arrived along Spain, France, Poland, Belgium, and others in disappointment. But this was before the Covid crisis. Why is the latter intervening in this transition discussion? Because the targets set by the EU directive are expressed as the ratio between the renewable energy used and the total final energy used. Due to the economic recession, the total demand for energy has obviously fallen and therefore the percentage of renewable energy has increased accordingly. As a consequence, the Covid-induced recession is (temporarily) saving the EU and its member states of being embarrassed by failing to meet their own targets. The media, environmentalist NGOs and politicians claimed loudly the fact that electricity produced by wind farms and solar panels now represent 22% of the total primary energy. However, this figure has to be compared with the only relevant figure for geopolitics, balance of payments and emissions, that is primary energy. What we see is that, for the EU-27, the sum of the intermittent renewable energy (wind and solar photovoltaic) only represents 2.5% of the total primary energy. For Spain, this figure is 3.9% and for Germany 4.3%; but, for France is not more than 1.4% of the total primary energy. In spite of that bare reality, for policymakers, the media, and the public at large, renewable energy remains synonymous with wind and solar photovoltaic.

Massive funding found its way into the development and deployment of wind and solar energy solutions. For example, in Spain the Fondo de Amortización del Déficit Eléctrico has committed huge debts with the London banks: at the end of 2019, the debt was 16.6 billion euros, and only in 2020. The Netherlands made some €4 billion available in direct subsidies. The report of the UN Environment Programme and Frankfurt School highlights that “A decade of renewable energy investment, led by solar, tops USD 2.5 trillion’. It precises that ‘Europe as a whole invested $698 billion in 2010 to first half 2019, with Germany contributing the most’, the large majority being for wind and solar power plants. I estimate that between 2000 and 2018, the EU and its Members States spent more than one thousand billion euros for promoting renewable energy, mainly wind and solar energy. But, let’s remember that despite this huge investment in the EU wind and solar energy represent only 2.5% of the total primary energy.

Contrary to the ongoing popular claim, this huge public financing shows that renewable energy is not competitive at all. If it had been, there would have been in 2001, 2009 and 2018 no need for EU directives to compel their production. Said otherwise, the very existence of such directives shows that forcing to produce a certain type of energy does not deliver results because at the end subsidies having to face a free market are unsustainable. But precisely, are we still in a free market?

The disappointment of the opening of the energy market policy

After years of discussion, in March 2002, at the EU Barcelona Summit, Prime Minister José Maria Aznar made a compromise with President Jacques Chirac to open the electricity market to competition and to the unbundling of electricity companies. This was considered as a breakthrough because, at long last, this monopolistic market would be broken and opened to competitors. As a consequence, any EU utility was allowed to invest in any Member State. What is the outcome of this political decision? Claude Desama, a former Socialist member of the EU Parliament and former rapporteur of this directive, is quite harsh on its final outcome. He recently published an article to assert that the EU electricity system is an ‘outdated model’. There are various reasons for this failure, but him – and I also – consider that the main one is that the EU obliged competing utilities to produce expensive renewable energy and to give this out-of-the-market energy a dispatching priority.

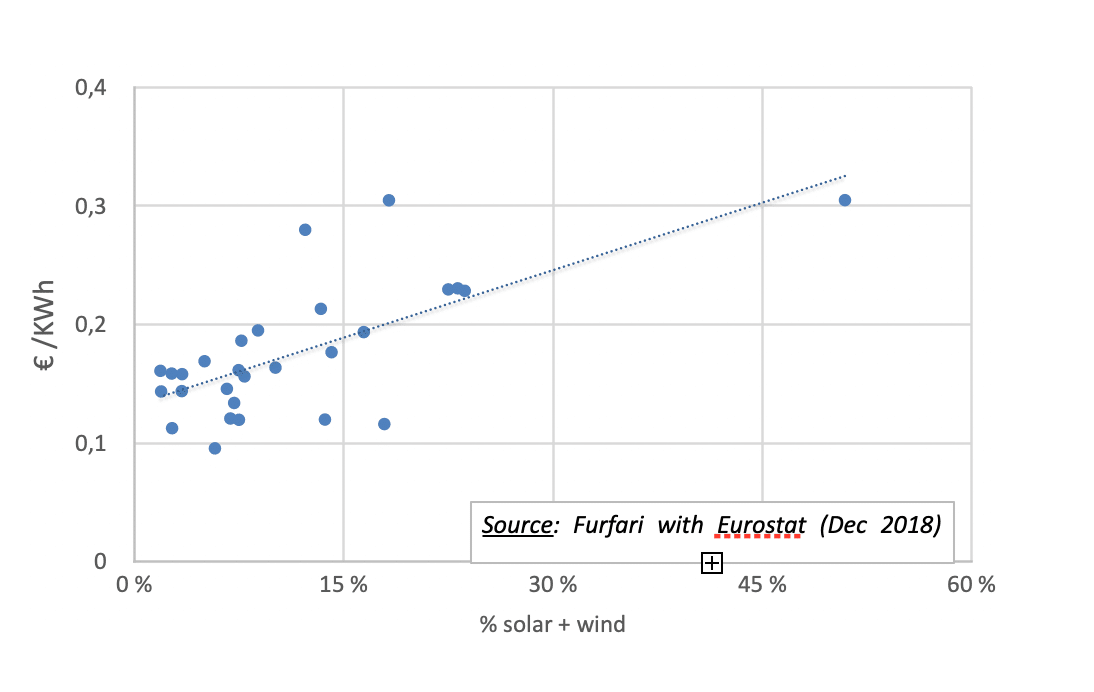

How can a market operate properly when there is obligation to do something that have no market meaning? The result is simple but not very well-known despite the fact that it has been published: an ongoing price increase for private and corporate consumers with a clear correlation between the price and the percentage of intermittent energy[7]. It is therefore no surprise that Germany and Denmark enjoy a high share of renewable energy, but also the most expensive electricity in Europe (see Figure 1).

We do not have time to elaborate on the failure of the biofuel strategy that the EU and its Member States initiated in 2009. Confronted with the inconveniences of this political decision – including for the environment – the directive has been modified twice to reduce the ambition of the initial scope. Finally, the directive ironically transformed the minimum objective of 2009 into a maximum as already explained in European Scientists. The slump is obvious.

Figure 1Correlation of electricity price for dwellings with intermittent renewable electricity production

Probably, the worst decision of the European Commission on energy in recent years is what it ventures to call the ‘A hydrogen strategy for a climate-neutral Europe’. As I explain in my latest book, ‘The hydrogen illusion’, the European Commission has ignored 51 years of high-level research, including by its own services, to try to implement a new policy to help the Germans meet their vision of the energy transition. I demonstrate, with the help of chemistry and physics, that the European Commission is making a major mistake in turning down decades of research on hydrogen. This hydrogen strategy is a mere ideological decision, which does not make sense at all from a scientific and economic points of view, except if high-temperature gas nuclear reactors (HTGR) will be one day commercially available.

Politicians should not play at being engineers

Politicians and bureaucrats should not try to ‘play at being engineers”. With the pretext of sustainable development and climate change, they pretend that they can impact the extremely complex energy system. But they cannot. They may decide spending money for influencing this or that technology, but the reality of the market is always remaining. Taxpayers money will be spent but without shaping the energy system.

The US nuclear industry is very active and spends their own money for creating the conditions for supplying massive electricity needs of the future. The Small Modular Reactor (SMR) technology is reaching the first-of-its-kind projects. President Obama has not intervened directly in this, but he created the conditions for the US authorities to swiftly adopt the safety rules for this new technology. He helped implement this crucial administrative part in nominating Steven Chu, a Nobel prize winner in nuclear physics, as Energy Secretary of its first term and then Ernest Moniz, a nuclear professor from the MIT for the same position during his second term. Everything is now in place for the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission to decide whether the market decides to buy or not this technology. But President Obama did not try to be an engineer. The same can be said for Georges Bush with the shale oil and shale gas production. These American successes demonstrate that governments have a role to play, viz. in regulation and safety but not in deciding which technology to oblige or mandate, this is the preserve of the Market (unless one considers that energy is now to be beyond the Market’s reach). In the EU, playing the engineer and discarding the Market led to many failures; one hypocritical example is the EU Members States refusing to produce shale gas but buying US shale gas.

However, governments have a role to play

Let me be clear: governments should play a role in research and development, but unlike what has been done in the last twenty years in the EU, they should stop deciding what about research should be. Few people know that, in the EU, politicians are hiding behind ‘experts’ committees’ to decide which particular technological sector should receive public support. The call for tenders contain tens of pages catalogues giving the precise details in which sector subsidies will be granted. For example, for the time being, intermittent renewable energy receives the lion’s share of subsidies for research and development in the EU, whereas supporting energy efficiency – critical to save energy and cut CO2 emissions – is the junior partner. In an ideal world, this may well be an unwise use of taxpayers’ money, particularly under the current circumstances.

One way to avoid this is that the research financing should not be given to a specific technology but to infrastructure and researchers, including by removing the VAT on all research equipment’s and expenditures. Leaving the laboratories and the industry decide where they perceive success is the key to progress. Sadly, and paradoxically given the huge EU investments in research, we cannot assume that for the time being the EU is a world leader in innovations. Politicians should not play the engineer even less the scientist.

Obviously, there is a role for governments to set rules for environmental protection. But this should be limited in fixing clear rules that must be complied with. For instance, if the EU really aims at reducing CO2 emissions, why is it that renewable energy is considered good and nuclear considered bad? In terms of both CO2 emissions and energy supply security, nuclear energy is a champion. Yet, in the Green deal communication and in the ‘Europe’s moment: Repair and Prepare for the Next Generation’ explaining how to spend the recovery fund of the European Commission, the word ‘nuclear’ is not even mentioned one…

And yet there is a role for the EU to play in the nuclear field. Several industrialised countries are progressing in the industrial development of SMR and HTGR (see here above). The ongoing pre-competition R&D cooperation is highly productive, but it will be interesting for the EU to have a more active role in coordinating the EU research in these sectors because the technology developers are no longer national companies but mostly international operating companies. Maturity for a pilot scale or even a demonstration project is at hand. The EU would be well advised to embrace it. This is not in contradiction with the previous paragraph because here it is not to finance micro projects but to accompany a strategy that needs to be driven and implemented by industry.

It is even more surprising that some local and municipal authorities are hoping to impact on energy geopolitics! Having led the way in 1994 in this area, I know that they have a role to play, but it should rather be on the energy demand side. Since energy questions are so popular, local politicians are tempted to appear as energy specialist to their local population. They are therefore willing to make decisions to help the energy transition. This is easier said than done. Their key role should be on the social side of energy, for example by helping to fight fuel poverty, which will increase with an all electricity cum renewable policy.

But deciding which type of fuels should be used is not a role for localities but for the industry while compiling with the environmental legislation. Mayors should rather work to make transportation in the city much more fluid in order to avoid pollution. I do realise that in the present mood, my proposal has no chance to be followed, but I cannot prevent myself from saying that what I have learned from my long experience as an engineer, an academic and a policy adviser.

The trial ahead for the energy politicians

My colleague specialised in nuclear energy, Prof Ernest Mund, and I recently wrote an article on the energy transition. Figure 2 shows that energy transition can only take place when we use small quantities of renewable energy. It shows that implementing the EU energy transition (right part of the graph) is more than challenging. Our conclusion is that the efforts for implementing the ongoing energy transition will be economically ruinous and will lead to failures. In an isolated word, this would already be painful for their Members States. But in a globalised and market-based, world where competitors instinctively turn to the sources of progress, the dramatic consequences for the European economies of such a strategy may well induce some Member States to loosen their ties with the EU for surviving, which would be very harmful for the European Union.

Figure 2 Changes in primary energy market share based on annual consumption of Mtoe/year (IEA and BP data for the world). From 17

Let’s recall again that the EU was born from the desire to provide its member states’ economies with ‘abundant and cheap’ energy (Messina resolution of June 1955). Today, the EU, because of its willingness to impose the fuel mix by EU legislation and by cherry-picking financing, is playing its very future with the slogan of energy transition. This transition will be difficult to achieve in the announced timescale; in particular cutting CO2 emissions by 55 or 60% by 2030, which is simply impossible (see my contribution to European Scientist in October 2020)unless the EU and its member states would decide a near-permanent lockdown. Table 1 gives the variation of the CO2emissions for a few EU Members States and also the remaining effort expressed in Mt CO2 to reach the objective of -60% in 2030 as requested by the European Parliament. The numbers are frightening’s for most of the Member States. For the EU-27 the expected is to multiply by five the annual reduction realised since 1990. This is just impossible by the size of the effort but also because the easiest solutions – the ‘low-hanging fruits” – have already been completed. It is just out of scope. The EU CO2 policy will simply be a total failure. Many would say the cure is worse than the disease.

Table 1 What policymakers decided regarding CO2 emissions (data of Eurostat June 2020)

| Member State | Reduction per year from 1990 to 2018 (Mt CO2) | Reduction compared to 1990 | Reduction per year to reach -60% in 2030 (Mt CO2) | Ratio of future effort to reach -60% to past results (%) |

| Austria | + 0,22 | +10% | -3,67 | 1647 (negative) |

| Belgium | -0,65 | -15% | -4,66 | 732 |

| France | -2,14 | -15% | -15,47 | 723 |

| Germany | -9,96 | – 26% | -29,97 | 301 |

| Italy | -2,95 | -19% | -15,23 | 517 |

| Poland | -1,30 | -10% | -15,82 | 1213 |

| Spain | + 1,84 | +22% | -16,09 | 875% (negative) |

| The Nederland | +0,17 | +3% | -8,80 | 5068 (negative) |

| EU27 | -26,47 | -19% | -134,49 | 508% |

In 2010, Vaclav Smil, a very respected American energy economist, demonstrated in his book ‘Energy Transitions’ that an energy transition couldn’t be done either easily or overnight, viz. within the deadlines set at the time by the Obama administration. This is even more so in the framework of the so-called geopolitical European Commission.

The EU must rapidly pull itself together; otherwise, it will fail, and its firms and citizens will suffer in the long term from the backwardness accumulated in the field of innovation (particularly in nuclear energy) compared with the USA, Russia, China, and even India.

A transition on the scale which is talked about presupposes an understanding of the issues, an absence of ideological prejudices and a coherent approach. And above all, despite the urgency claimed by the activists, it takes time. And governments, with a horizon of four or five years, are not good at that. Energy is an issue for science and technology, not of short term politicians.

[1] F. Krause, H. Bossel et K-F. Müller-Reissmann, ‘Energie-Wende. Wachstum und Wohlstand ohne Erdöl Und Uran’, S. Fischer, 233pp, 1980,

[2] COM(2006) 848 final

[3] https://www.cnmc.es/expedientes/infde00220

[4] Netherlands doubles 2020 green subsidies in rush to hit climate goals. Reuters, 4 March 2020, available at https://www.reuters.com/article/us-climate-change-netherlands-idUSKBN20R2DT

[5] UNEP and Frankfurt School, Global trends in renewable energy investment 2019

[6] Claude Desama, Le système électrique européen est un modèle caduc, La revue de l’énergie, Juillet-Août 2020

[7] Samuel Furfari, L’électricité intermittente, Une réalité et un prix., Science-climat-énergie, 31 août 2018

[8] Samuel Furfari, Biofuels a long standing illusion, European Scientist, 2018, https://www.europeanscientist.com/en/features/biofuels-a-long-standing-illusion/

[9] European Commission, A hydrogen strategy for a climate-neutral Europe, COM/2020/301 final, 8.7.2020

[10] Samuel Furfari, The hydrogen illusion, , ISBN 9798693059931

[11] https://www.nrc.gov/reactors/new-reactors/smr/nuscale.html

[12] Samuel Furfari, Interdiction en trompe l’oeil : la France, premier importateur européen de gaz de schiste américain, Atlantico, 2.8.2019, https://www.atlantico.fr/decryptage/3577230/interdiction-en-trompe-l-oeil–la-france-premier-importateur-europeen-de-gaz-de-schiste-americain-samuele-furfari

[13] European Commission, The European Green Deal, COM(2019) 640 final of 11.12.2019

[14] European Commission, Europe’s moment: Repair and Prepare for the Next Generation, COM/2020/456 final of 27.5.2020

[15] I had personal example of that in Spanish Anthonomus Community when I was in charge of energy relations with regions and local authorities.

[16] Martin Fernaes Prado and Luis Domingo Castro, City Policies and the European Urban Agenda, Palgrave MacMillan, 2019

[17] Samuel Furfari, Ernest Mund, Transitions technologiques et Green Deal, La Revue de l’Énergie n° 652 – septembre-octobre 2020

[18] Messina Resolution, 1-3 June 1955

[19] Samuel Furfari, Climat et Parlement européen : manque de calcul ou démagogie ?, European Scientist, 15.10.2020, https://www.europeanscientist.com/fr/opinion/climat-et-parlement-europeen-manque-de-calcul-ou-demagogie%E2%80%89/

[20] V. Smil, ‘Energy Transitions – History, Requirements, Prospects’, ABC-Clio, 170pp, 2010

This post is also available in: FR (FR)DE (DE)

True about energy, but also applicable to many other areas, the article takes advantage of what a rational scheme would be:

Where politicians, listening carefully and with a well developed critical mind to their people determine what is desirable.

Where scientists would suggest appropriate process to meet these demands, indicating what is actually possible and what is not (or very relatively possible).

Where men with practical skill (engineers, agronomists, doctors, architects, etc.) would design the means (machines, systems, methods, etc.) to make these orientations a reality.

Where people, using feedback, by their acceptance, their call for modifications, or simply their rejection, would close a real logical loop.

The article finds that, on the contrary, this logical chain is most often reversed or deviated, the energy domain illustrating these disorders in a very convincing way.