As the 2025 edition of the World Economic Forum in Davos opens its doors on Monday, Swiss engineer and essayist Michel de Rougemont revisits a McKinsey report titled ‘The Hard Stuff: Navigating the Physical Realities of the Energy Transition.’ Published in mid-2024, this report will undoubtedly be reviewed during the event… Will we witness a return to reality regarding decarbonization? That’s the question the author poses.

Even if there are reservations about McKinsey, the global strategic advisor, it must be acknowledged that it is a rich source of information and analysis. In its role as a substantial supporter of the World Economic Forum (WEF) in Davos, it published a major report (1) last summer which, at last, is dedicated to the physical realities of the energy transition.

This report has three qualities: its origin, its content and its scope. No one will have the elements or the courage to question the competence of its authors, and we must realise that no paper tiger, speech or law, will achieve decarbonisation, either in magnitude or in time. What we understand from the report is that the technologies to be implemented have so many complexities and shortcomings that decarbonisation and energy transition, if at all achievable, will take a long time, with no predictable outcome.

It is sufficient to read the Executive Summary of this report as it is even comprehensible to the scientifically and technologically handicapped. It is remarkable that it openly acknowledges that the efforts made to date are nothing more than low hanging fruits and that it is not enough, even on a massive scale and at full speed, to invest in current technologies in order to achieve the necessary transitions. On the contrary, it could prove counter-productive if the necessary progress is pre-empted by partial, flawed solutions that become obsolete too quickly.

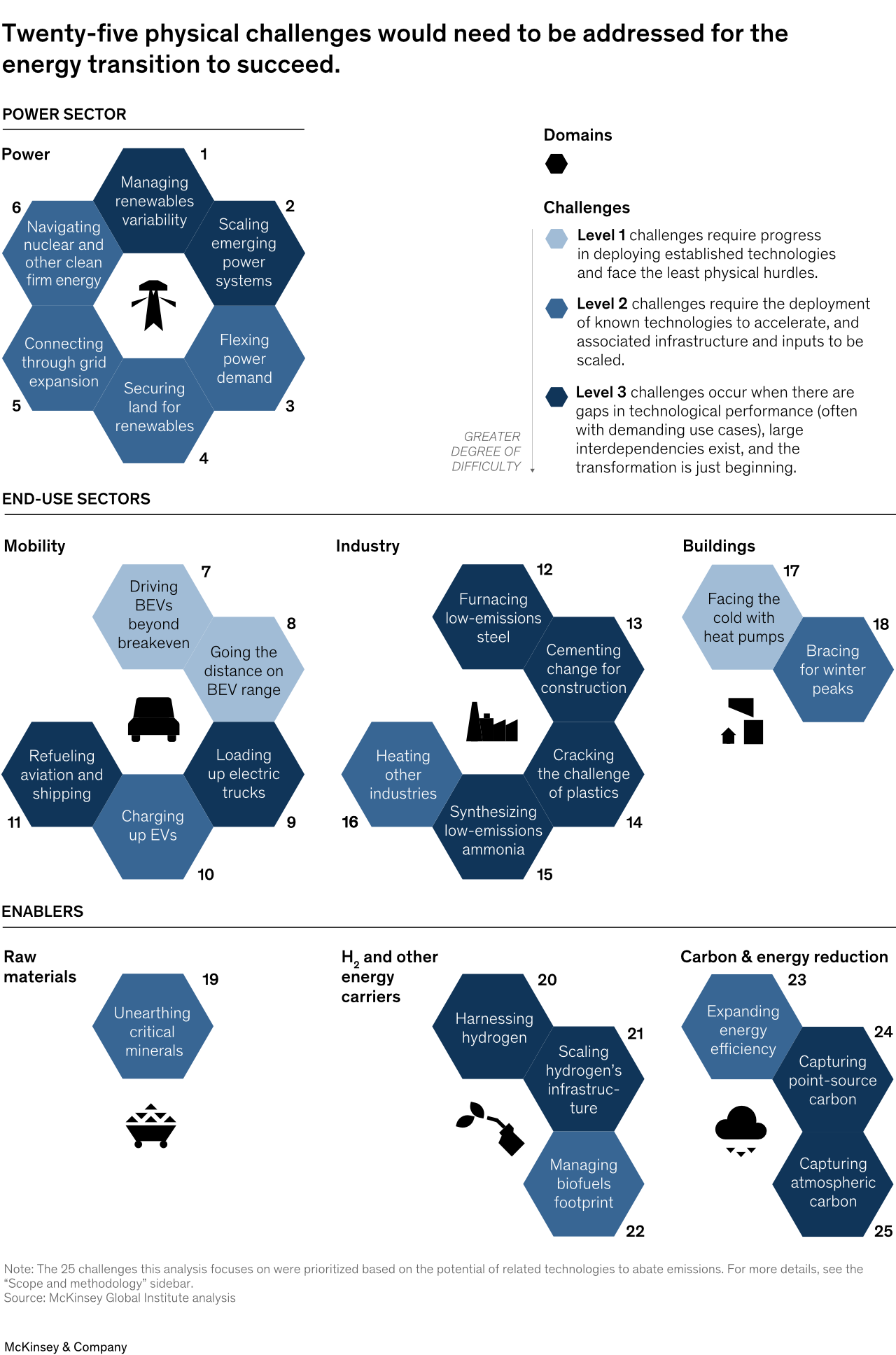

The 25 Physical Challenges of the Transition

The whole problem is addressed by identifying twenty-five challenges (see figure above), only three of which consist of correctly deploying established technologies that are not encountering any major obstacles, even if the size of this deployment is not trivial (number of electric vehicles and heat pumps). Ten others require not only the acceleration of the deployment of known technologies, but above all the scaling up of the corresponding infrastructures (e.g. electricity grids) and the availability of the raw materials (e.g. lithium) associated with them. And as for the remaining twelve challenges, frankly, nobody knows today what shape they will take, because current performances have gaps – a euphemism for “not at all up to scratch” – and because they require major interdependencies to be taken into account. For example, the industrial pillars of our modern society are in this category: steel, cement, plastics and ammonia; it also includes managing the intermittency and seasonality of so-called renewable sources of electricity.

Some dead ends

Beyond this necessary categorisation of challenges, what is clear from reading this report is that objectives such as “net zero by 2050” or “no more than 1.5°C” or “no more combustion engine vehicles as of 2035” only serve ill-conceived policies that are only binding on those who believe them, not on those who make them believe them. This report also avoids a major pitfall, that of economic evaluation. This is regrettable, as it is of the utmost importance, but it must be acknowledged that the exercise is impossible, at least if one wishes to carry it out honestly. In fact, the billions and other trillions that are thrown at decision-makers do not motivate many serious investors: that is why public funds are called upon, fed by taxpayers, and which can only remain well below requirements and without the expected leverage effect – one more waste of resources.

Change plan and adapt

There is an alternative to this grandiose circus: abandoning the urgent need for an energy transition at all costs, abandoning the pretence of planning for a future that is no less uncertain than ever, encouraging R&D at the highest level without prescribing results while cutting off funding for insignificant projects, and, above all, adapting to the effects of inescapable global warming. It’s a vast programme, and one that calls for sobriety on the part of leaders thirsting for sad glories because they are futile. Let’s give McKinsey credit for having the courage to stamp its feet in the puddle, which is bound to splash out on an audience more accustomed to confirmation bias than forthright criticism.

What if the ‘spirit of Davos’ started to blow in the right direction, that of reality?

(1) https://www.mckinsey.com/mgi/our-research/the-hard-stuff-navigating-the-physical-realities-of-the-energy-transition

Further reading

SMRs are the key to Europe’s climate goals and energy independence

Will the EU put a super-plough before soil conservation goals?

Technology has a role to play in CO₂ mitigation Tilly Undi (Interview)

This post is also available in: FR (FR)