Gene-edited CAR T cells caused no adverse effects in three cancer patients who participated in a recent Phase I Clinical trial, the first of its kind in the US. The results, published on 6 February in Science, show the procedure is both feasible and safe, representing an important milestone toward the clinical use of CRISPR-engineered T cells (1).

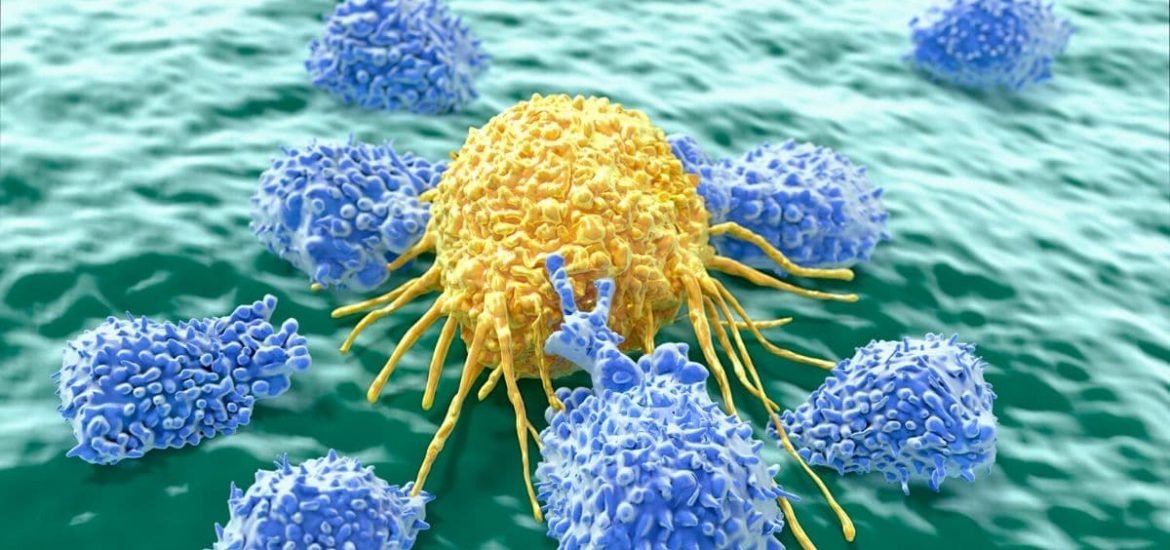

The field of cancer immunotherapy is advancing at a rapid pace. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells, also known as CAR T cells, are immune cells — taken from either the patients own blood or a donor — that are reprogrammed to target a specific protein, in this case, receptors on cancer cells. Once the cells have been reprogrammed, they are reinfused back into the patient’s blood. By genetically engineering T cells to recognize cancer cells, the immune system can more effectively target and destroy them.

Now, scientists have taken this one step further by combining the CAR T approach with CRISPR-Cas 9 to make the modified T cells even more potent. The researchers from the University of Pennsylvania and Stanford used CRISPR to further modify T cells by deleting three genes: two of the genes interrupt the CAR T cell’s ability to target cancer and the other encodes for the PD1 protein, which also dampens the body’s immune system response; in addition, knocking out the first two genes is also thought to boost the expression of another cancer-targeting receptor on T cells.

The discovery of CRISPR-Cas9 in 2012 generated a lot of excitement. But whereas CRISPR-based technology has become an important tool for research and innovation, safety concerns have hindered its plausible use as a therapeutic mechanism for preventing and treating human diseases like cancer. Now, the much-touted tool might finally have a chance to live up to its hype.

Preliminary results presented at a conference in December last year were promising. In the small trial, two women with multiple myeloma and one man with sarcoma, all in their 60s, received the supercharged CAR T cells. A fourth patient in her 30s who was supposed to be involved in the trial died before the cells were ready for infusion.

The latest results suggest limited therapeutic effects. The man’s tumour did shrink, however, his cancer eventually progressed, as well as the cancers of both women. One of the women has died since receiving the treatment. But importantly, the cells were not intended as a cure, but rather to test their safety. And in this respect, the trial was a success.

The CRISPR gene editor did cause some “off-target” cuts and unintended deletions, but more than 90 per cent were right on target. Moreover, the efficiency of CRISPR has been improved since the versions used to create the cells for the trial, so more accurate editing might be achieved in future trials.

Nonetheless, the modified CAR T cells appear to be safe and long-lasting. In fact, the cells survived much longer than expected. Modified cells were still circulating in patients’ blood nine months later, which is longer than similar studies showing that alone, CAR T cells only last around two months.

(1) Stadtmauer, E.A. et al. CRISPR-engineered T cells in patients with refractory cancer. Science (2020). DOI: 10.1126/science.aba7365

(2) Stadtmauer, E.A. et al. First-in-Human Assessment of Feasibility and Safety of Multiplexed Genetic Engineering of Autologous T Cells Expressing NY-ESO -1 TCR and CRISPR/Cas9 Gene Edited to Eliminate Endogenous TCR and PD-1 (NYCE T cells) in Advanced Multiple Myeloma (MM) and Sarcoma. Blood (2019). DOI: 10.1182/blood-2019-122374