The Sars-Cov-2 pandemic underscored that French medicine could tear apart over opinions. However, this “medicine of opinion” was not born with the pandemic. Rather, emergency situations unveil the cognitive and heuristic processes at play, as well as the decision-makers intentions, behind this worldwide medical upheaval. This is what I analyze.

The birth of medicine

Healthcare, and medical practice as a whole, emerge from the evolution of innate behaviours of altruism existing in the mammalian lineage. A severely injured wild animal dies most often. Humans changed this fate. Immobilizing the fractured bone, and protecting and feeding the patient allows for the healing of bones as large as the femur. This example cited by Mrs Margaret Mead as an essential anthropological discovery helps to ask essential questions (1). The evolutionary development of neurobiological centres of human values, explains the emergence of care and medicine in homo sapiens (2). Since the use of medicinal plants and the first life-saving surgical procedures, including the most exceptional such as trepanation (6000 years BC) (3), medicine developed through the convergence of empathy for the suffering of others and the most rational observation in order to find efficient treatments. Further, the evolutionary fixation of ‘humane’, altruistic values in neurobiological centres played a part in the development of healthcare and medicine in Homo sapiens. (4) .

Hippocratic medicine was the first to set the imperative of ‘primum non nocere’ at the heart of practice and its decision-making. No form of empathy could possibly justify adding to one’s suffering without bringing a critical edge. The history of medicine, punctuated by protrusions of intelligence and boldness, carries on until seeing a turning point in the nineteenth century. The introduction of experience as a means to understanding disease, notably through Claude Bernard’s practice, paves the way for physiology to develop. After the discovery of DNA by Watson and Crick, ‘modern’ medicine becomes a prolonging of molecular biology. The adventure of modern medicine consists in working out the mechanisms behind disease and the appropriate therapeutic solutions, both at the molecular scale. This adventure recently accelerated along the lines of Moore’s Law, as Artificial Intelligence (AI) became an essential means for thrusting innovation (5) .

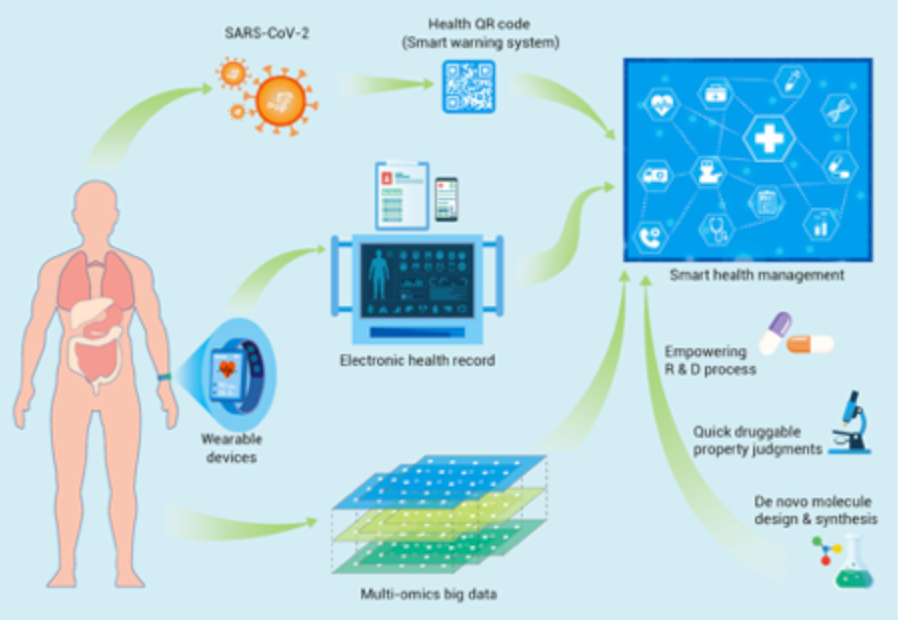

Figure N°1: AI is omnipresent in personalized medicine (6) .

In this context, a medicine where opinion grounds practice stifles scientific advances

Before the irruption of molecular biology, medicine was essentially anatomical and empirical, dominated by the disregard for the core physiopathological mechanisms at play in disease. Hence why each doctor would draw solely on personal experience and various theories, either outdated or invented. This also explains why a corpus of ‘beliefs’ still coexists with the evidence brought by modern medicine.

Renouncing a power based on unscientific data rather than adopting a practice based on shared and evolutionary evidence

In the public debate, the opinion of certain people, often occupying life-long positions in academia, too often prevails on scientific publications, experimental results, and particularly on unfalsifiable results from clinical trials. These data, formerly hard to access or interpret, are easily retrievable today. The general standard is high, especially so in prestigious journals. Contrary to those reliable sources, the aforementioned people often stay in a fixed conception of medicine because they relay a view of medical topics as definitive. They tend to justify their affirmations by drawing on theories rather than the recent facts, results, and the probability of falsification of tested hypotheses.

A medicine from opinion in a society where intentions predominate (7)

From this perspective, part of French medicine did not succumb to this trend towards opinion but rather remained unchanged. However, even the ‘original’ kind is too attached to an opinion, in a world that is increasingly influenced by science and the Popperian paradigm. (8) . To explain this, Laetitia Strauch-Bonart’s essay “De La France” (About France) is insightful. It emphasizes a typically French tendency to prefer inference to deduction; one which exists in all domains of public debate. Certain doctors tend to put forth their ideas, concepts, and theories before the facts in a purely inductive scheme. This inductive scheme is an obstacle to the unbiased assessment of medical solutions. The denigration of proof or the misunderstanding of those can be explained for the most part by the a priori choice between options: that is, adopt a theory by inference first, then ‘cherry pick’ data to validate it. This bias is relatively widespread.

How do doctors across the world think about medicine?

The empiricism taught in the Schools has definitively demonstrated its incapacity to innovate and bring reproducible results. As a result, doctors organize in such a way that biological subjects or clinical trials are tackled with a method and utmost transparency between teams. This is how the corpus of knowledge and discoveries build up. In the international medical community, particularly Anglo-Saxon, clinicians test hypotheses by designing and conducting experiments that lead to measurable facts called ‘results’. Those results are evaluated by probabilities (e.g. Pearson’s Chi-Square Test) to know their validity, specifically through investigating the error risk and causality links. Their heuristic approach is deductive. Let us focus on the matter of such hypotheses.

In France, economic, political, and social structures consolidate the predominance of opinion over evidence

The 1958 Debré reform created a French outlier. The triple function of clinical care, research, and teaching was locked by the hierarchical authority of chieftainship and life-long nomination. It is impossible to grant any more power to the state. This model, dear solely to the concerned parties, is in ruins and forsaken by most. The first evidence: an individual cannot perform outstandingly throughout their life. It is highly probable that they do not even temporarily do so. Second evidence: they can, in exchange, be good soldiers to the academic status quo, the bureaucratic extensions, and State medicine. This not entirely blocks the system but consolidates in some doctors the conception of a definitive medical truth based on an authority argument. Yet, this is untrue: it is not the opinion of scholars which constitutes proof, but rather the critical study of experimental and clinical results, as aforementioned.

Pandemic and uncertainty, the irrational choice of opinion

This partly explains why, during the Covid pandemic, the trust of the people was dented so fast. The system is completely ill-adapted to uncertainty as well as personalized, precision, and ambulatory medicine. In fact, it is based on hospitalization, on the opinion of several scholars and experts appointed for life, and on the absence of assessment regarding results and the quality of care. During the pandemic, certain scholars put their ‘point of view’ forward, with allegations of certainty devoid of any rational basis whatsoever. These served as instances of ‘authoritative arrogance’. Whether it be those that cannot think outside of the State medicine symbolized by the HAS, or those that through the same kind of reasoning trap themselves in erroneous theories, both parties are conflicting with evidence-based medicine. When medicine evolves slowly, or does not evolve, this ‘medicine from opinion’ is tenable. In the middle of the acceleration of discoveries we are currently experiencing worldwide, medicine of opinion does not make sense and can lead to consequences for our patients. Indeed, it is the patient who bears the risk when a caregiver takes a gamble instead of intervening with caution.

The principal flaw of inductive reasoning, or rather of the choice of inference over deduction in medical practice, is to confuse the emergence of an idea with the evidence that drove it. This emergence is, in the best case, nothing more than the hypothesis to test, and evidence is born out of the inability to falsify the hypothesis. And so on.

This unique model leads to relativism, but where does it come from?

A State model is unique and rigid

The situation that we are experiencing in France is the result of an unfortunate cultural exception widely fed by the statism in academia, the medical practice, and the faculties of State medicine. It is urgent to let research be proofread by peers unrelated to the researchers in question; it is critical that academia be diverse while staying faithful to its standard of excellence, that is, results. However, the obstacles to research and innovation, caused by the clamping of the hospital-university system, are too substantial to overcome. Back when innovation was rare, the externalities of such a system were weak. Since medicine hinges mainly upon novelty, we rely more and more on the flux of discoveries and innovations coming from abroad. This is not due to the purported inability to harness innovative topics, but rather to a series of hindrances, obstacles, and prohibitions. We mentioned earlier that some of those are by-products of the academic structure. However, the rest of these springs from the administrative superstructure seen as the sum of defensive, ‘ecological’, and financial layers that the state, the only power holder, has set in motion. At the heart of this superstructure lies the healthcare system, and this setting increasingly hinders the optimal functioning of the latter.

The negative externalities of the model

The blockage of the slightest evolutionary thought and its rational mechanisms, regardless of their validation by the current research consensus, leaves a tremendous space for the worst alternative: fake news and conspiracy theories. By these, we refer to the contesting of the weather, between other observable facts, based on a “worldwide conspiracy” and a “victimhood paranoia” denouncing Big Pharma, the vaccine trial results, etc. This trend is led by people that never cured a patient, or, far more concerningly, unscrupulous doctors whom people trust at their word. There is also a smaller form, yet as deleterious, of denying reality: relativism. To escape this dilemma, there is no need for a commission for transparency (9) or speech without action (10 ).

Rather, we need to open up to civil society and free academia, medical practice, and the scientific world from the State and its institutions. This, I believe, would be a true Renaissance project.

Nota bene: This article was translated by Arthur Assant, a Human Sciences student at UCL

(2) https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00199/full

(4) https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00199/full

(5) https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34877560/

(6) https://www.cell.com/the-innovation/fulltext/S2666-6758(21)00104-1?_returnURL=https%3A%2F%2Flinkinghub.elsevier.com%2Fretrieve%2Fpii%2FS2666675821001041%3Fshowall%3Dtrue

(7) https://www.lemonde.fr/idees/article/2014/06/13/etiquetage-alimentaire-les-bonnes-intentions-ne-font-pas-de-bonnes-politiques_4437595_3232.html

(8) https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11191-021-00317-9

(9) https://www.elysee.fr/emmanuel-macron/2021/09/29/les-lumieres-a-lere-numerique-lancement-de-la-commission-bronner

(10) https://www.atlantico.fr/article/decryptage/la-commission-bronner-verites-officielles-et-science—l-equation-impossible-guy-andre-pelouze

This post is also available in: FR (FR)