Contrary to previous assumptions about stem cell development, a new study published on 16 May in Nature suggests that all cells of the intestinal wall — and not just those deemed “stem cell precursors” — can contribute to the pool of stem cells in the gut (1).

In other words, every cell in the gut seems to exhibit this so-called plastic behaviour, which simply means the immature cell has the ability to transform into other cell types — including stem cells — depending on the surrounding environment – whether they are in the right place at the right time.

Adult stem cells are found in virtually all tissues and organs of the human body and usually reside in a “niche” – an area with good blood supply to support their rapid growth and important functions. Throughout life, from birth and through adulthood, the job of stem cells is to maintain tissues. And also repair damaged ones.

For example, skin cells and other organs are continually replenished by a nearby pool of adult stem cells – and the same is true of intestinal cells. But where do these stem cells come from?

Fetal stem cells give rise to adult intestinal stem cells. But scientists wondered whether other intestinal stem-cell precursors exist and might contribute to the intestinal stem cell niche.

Monitoring the development of intestinal cells

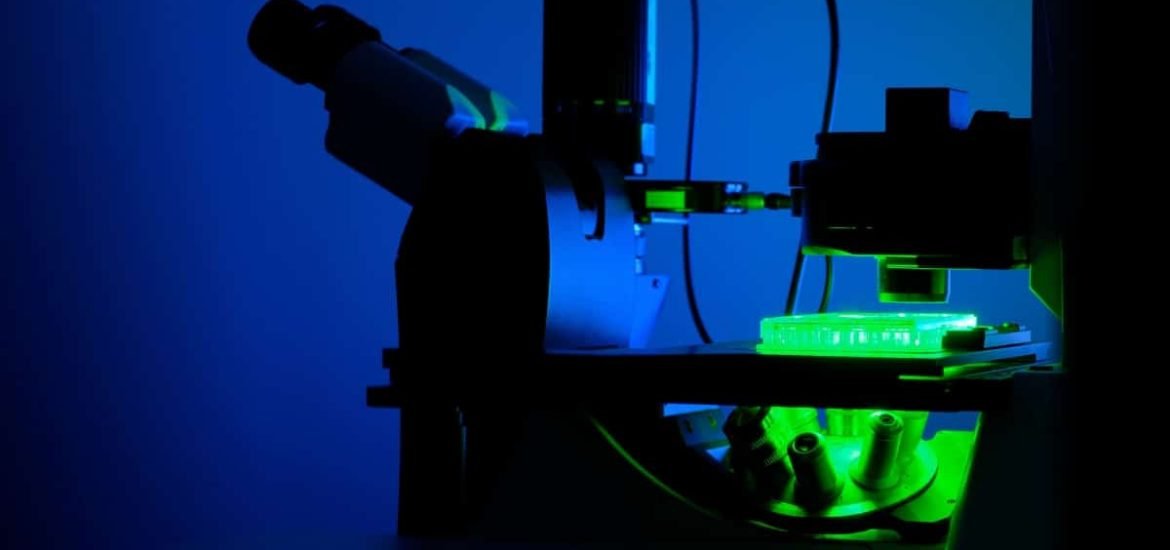

With the aim of better understanding what controls the destiny of intestinal stem cell, the researchers from the University of Copenhagen and the University of Cambridge used state-of-the-art cell imaging techniques, along with a bit of mathematical modelling, to study the development individual intestinal cells of mice.

By using luminescent proteins, they were able to monitor the immature intestinal cells under the microscope as they developed. Surprisingly, they found that the entire population within the intestinal stem cell niche could not be explained by the fetal stem cells alone. Therefore, cells located in other parts of the intestine must also be contributing to this stem cell pool.

What controls a cell’s fate?

Scientists previously believed a cell’s potential to become a stem cell was predetermined. However, as the authors write, “stem-cell identity is an induced rather than a hardwired property”. This means that signals from the surrounding environment may, in fact, determine their fate. Next, they hope to uncover the exact signals required to turn cells into stem cells.

This new information could make it easier to coax cells in the right direction, for instance, induced pluripotent stem cells. And could open up the door to novel — and possibly more effective — stem cell therapies, to treat non-healing wounds, for example. Transplanting new, healthy stem cells could help repair or replace damaged tissue.

(1) Guiu, J. et al. Tracing the origin of adult intestinal stem cells. Nature (2019). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-019-1212-5