A paper published on 5 September in Nature, has presented a new technique that can turn wound cells into new skin cells. The potential treatment that involves transforming cells in an open wound into stem-like skin cells that can generate new healthy skin. The cells are reprogrammed in vivo into a stem-like state that can potentially heal the damaged skin. This approach could also be useful in numerous other situations in which skin regeneration is impaired including ageing.

Large cutaneous ulcers penetrating through several layers of skin ― caused by severe burns, bed sores, and diabetes ― represent a complex clinical problem and are becoming increasingly common owing to an ageing population. Current treatments for this common cause of morbidity include surgical interventions such as skin grafts, which often cannot cover the entire area of damaged skin, or transplanting lab-culture epithelial cells, which is a time-consuming process.

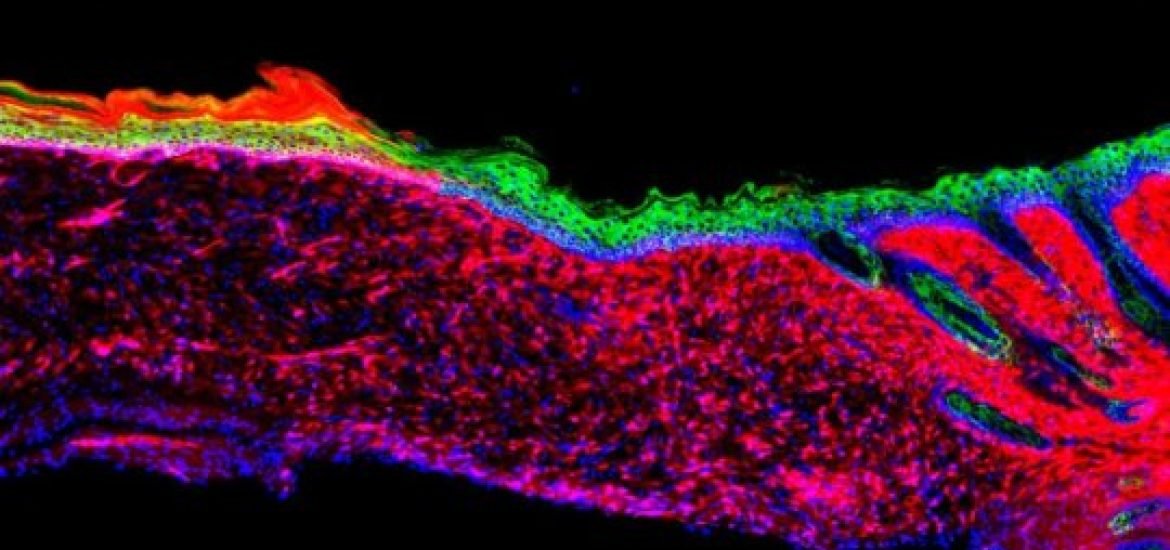

Normal wound healing involves migration of stem and progenitor cells (basal keratocytes) from deep within the tissue or neighbouring healthy skin to the site of injury where they transform into healthy epithelium ― the outer layer of skin ― in a process called re-epithelialization. Often with large or severe wounds, these cells types are not efficient enough to heal the entire wound or are no longer present. In this case, the cell types that do migrate into the wound are mainly involved in inflammation and rapid closing of the wound, and therefore generate scar tissue rather than healthy skin.

Based on recent advances in cell reprogramming, researchers at the Salk Institute in San Diego, California wondered whether the could coax any cell type, in particular, scar-forming cells, into the stem cell-like basal keratocytes in vivo. To test this theory, they identified 55 potential “reprogramming factors” (proteins and RNA molecules) ― distinct factors associated with basal skin stem cells. Then, using a trial and error approach, they whittled this down to four candidate factors ― DNP63A, GRHL2, TFAP2A, and MYC.

The team then loaded these “genetic instructions” into retroviruses, which are used to load the information into target cells, and used them to topically treated mice with skin ulcers. Within 18 days, a complete layer of cells covered the wound and after six months, the newly regenerated cells behaved like healthy keratinocytes.

According to the authors, these findings “constitute an initial proof of principle for functional in vivo regeneration of not only specific and individual cell types but also of a three-dimensional functional tissue in mice. But they also note that “the inflammatory status of the wound or other clinical features of the patient may affect reprogramming.” More studies are planned to optimize the technique and they will need to determine the long-term safety and efficacy of the treatment before it can be used on humans in the clinic.

(1) Kurita, M. et al. In vivo reprogramming of wound-resident cells generates skin epithelial tissue. Nature (2018). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-018-0477-4

Image source: Kurita, M. et al. Nature (2018).

Thanks for this blog, it’s great to know that such advances are taking place in cell reprogramming.