It is believed that human cartilage cannot regenerate itself, or at least, only to a very limited degree. That’s why repetitive joint injuries due to sports or trauma often lead to the breakdown of cartilage and eventually, osteoarthritis. But scientists have now discovered a “salamander-like” regeneration capacity in human cartilage, according to a new study published on 9 October in Science Advances (1).

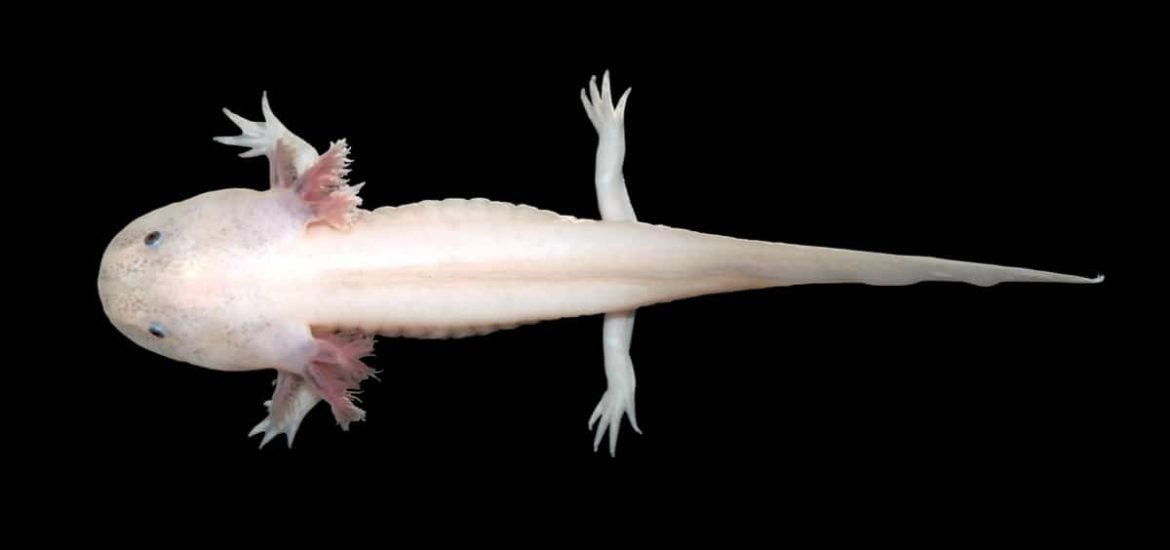

Some animals, like zebrafish (Danio rerio), axolotl (Ambystoma mexicanum; pictured), and Bichir fish (Polypteridae), can regenerate whole limbs. And the regulators of regeneration in the salamander limb appear to also be the controllers of joint tissue repair in the human limb, which lead author Dr Ming-Feng Hsueh of Duke University refers to as “our ‘inner salamander’ capacity”.

The team of researchers used so-called “internal molecular clocks” to determine the age of proteins, based on how many times an amino acid — the building block of protein — has been converted into another type of amino acid. As you can probably guess, new proteins have few conversions, whereas older proteins have undergone this process many times. And this idea allowed them to determine the age of proteins (mainly collagen) in human cartilage.

They discovered that the age of cartilage depends largely on location. For instance, ankle cartilage is “younger” than the cartilage in the knee. And cartilage in the hips is even “older”. This may help explain why ankle injuries typically heal more quickly than the joints farther up the leg. Indeed, hip injuries take much longer to resolve and often lead to arthritis.

Interestingly, they found that much like with the salamander and zebrafish these healing and ageing processes are dependent on something called microRNA — an evolutionary artefact that may give humans the capacity for joint tissue repair. In other animals with the capacity for limb regeneration, microRNA activity was also found to be location dependent. And in humans, microRNA activity varied significantly and was higher in the ankle compared to the knee and hips. In addition, the activity was higher in the outer layers of cartilage than in the deeper layers.

“If we can figure out what regulators we are missing compared with salamanders, we might even be able to add the missing components back and develop a way someday to regenerate part or all of an injured human limb”, says senior author Prof Virginia Byers Kraus. She also suggests this process is “a fundamental mechanism of repair that could be applied to many tissues, not just cartilage”.

While the results do not suggest that scientists have figured out how to regrow human limbs, the findings at the very least provide a basis for exploring novel cartilage regeneration strategies. The researchers suggest that microRNAs could be developed as medicines to prevent, slow, or possibly even reverse arthritis.

(1) Hsueh, M-F. et al. Analysis of “old” proteins unmasks dynamic gradient of cartilage turnover in human limbs. Science Advances (2019). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.aax3203